Employees are increasingly demanding flexibility and choice for where (and when) they work. What strategies can landlords implement to adapt?

In the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, the negative sentiment regarding the prospects of office properties was influenced by lockdowns, empty offices, and a better-than-expected short-term outcome of the work-from-home (WFH) experiment. However, with a prolonged WFH period, the negative aspects of this model as a fulltime approach have become evident and have balanced the consensus.1

Employees yearn for a higher degree of flexibility and choice when it comes to time spent in the office, compared to working remotely. Because of this, more employers are adapting a hybrid work model in which in-office and remote work is split. While the level of flexibility will vary by industry and company, in aggregate, demand for flexibility from office users is set to rise.2

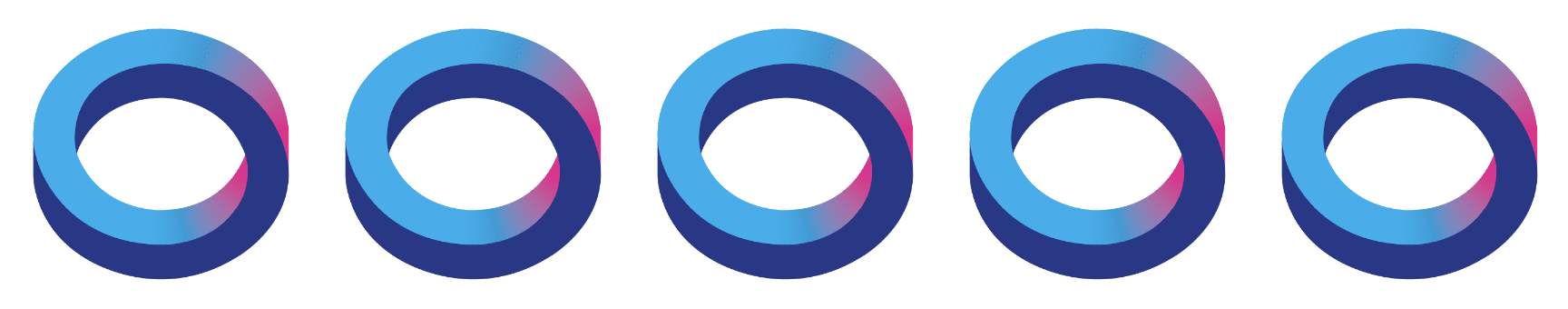

Coworking providers have been offering this type of flexibility for many years and have enjoyed a tremendous growth over the past decade.3 In the early stages of their evolution, coworking companies were focused on the membership model. Landlords perceived these companies as saviors because they typically leased otherwise less desirable space in older office properties or on lower floors.4 When coworking companies increased their focus on the enterprise model and began to sublease space in higher-end properties to larger corporate clients, it developed a conflict of interest for landlords. As a result, these landlords increasingly consider such flex office providers as competitors.5

1. TRADITIONAL LEASES WITH COWORKING PROVIDERS

Traditional lease agreements with coworking companies provided landlords with some sense of security for their future cash flow via long-term leases with fixed rent payments—as well as benefitting from a strong leasing market fueled by the rise of coworking. For example, in 2018, these leases accounted for 11% of Manhattan’s leasing activity, rendering WeWork the largest private office tenant in that market, with an overall occupancy of 5.3 million SF.6 By the end of 2019, coworking providers occupied around 18 million SF (3.8%) of Manhattan’s office stock, and WeWork accounted for more than half of that.

Still, there were some risks and disadvantages that came with these direct leases. Long-term liabilities for coworking providers with short-term income results in a duration mismatch that elevates bankruptcy and renegotiation risks for owners.7 Most lease agreements were structured as special purpose vehicles with very limited or no credit support.

In the rare case of a parent guarantee, the entire lease liability was not covered, and was depleted over the first couple years of the term. The landlord expectation, or hope, was that larger coworking providers would not abandon selective locations to avoid reputational risk. This hope did not materialize; even the largest global coworking providers—Regus and WeWork— abandoned a meaningful subset of their traditional leases and renegotiated many into partnership agreements. Throughout the pandemic, several flex providers in Manhattan returned 5 million SF to their landlords, representing almost 30% of the island’s pre-pandemic coworking inventory. With that, Manhattan’s coworking share decreased from its 2019 peak of 3.8% to its current 2.9%. However, in Q1 2021 alone, WeWork signed agreements for 1.2 million SF of new flex space.

Further, enterprise usage creates direct competition with vacant spaces within the same or competing buildings. An increasing number of troubled coworking providers are either closing locations; trying to lease their vacant floors to enterprise tenants who could be direct landlord tenants; or adding their vacant spaces on the traditional sublease market. This activity is so prevalent that brokers are now tracking direct vacancy, sublease vacancy, and more recently, shadow vacancy from coworking companies.8

As bankruptcy risk is amplified with an increased share of coworking leases within a building or portfolio, the pre-pandemic consensus was that office buildings with more than 20% of coworking exposure are gradually experiencing a price discount for this portion of their income.9 Recently, investors and lenders are scrutinizing coworking exposure even more. For instance, at the height of the lockdown, some lenders even fully disregarded coworking income as a conservative base case for their lending base.

2. PARTNERSHIP AGREEMENTS WITH COWORKING PROVIDERS

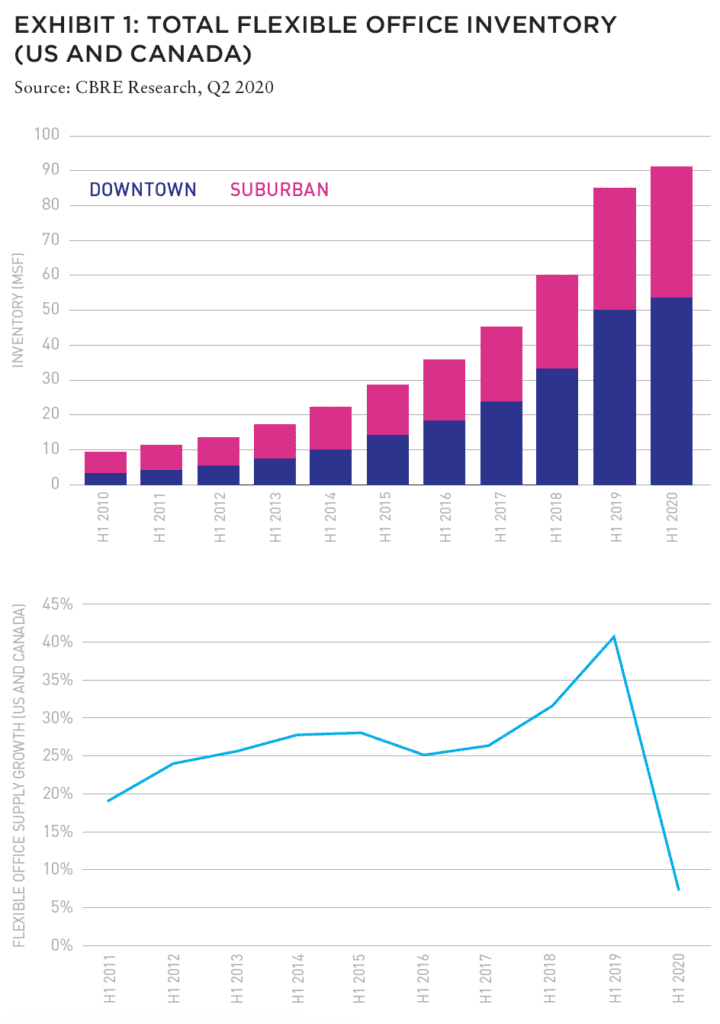

Partnership agreements allow landlords to participate in the upside in exchange for (a) covering most or all of the upfront tenant improvements and (b) limiting the downside risk of fixed long-term lease obligations for the coworking partner.12 These structures are evolving and range from complex profit-sharing agreements, simple revenue-sharing agreements similar to percentage rents in the retail sector, to management agreements on a fee basis. These arrangements decrease the conflict of interest between the two partners. There is a clear consensus that partnership agreements will continue to make up a larger share of the coworking arrangements. On a relative basis, Industrious— another leading coworking company—has been a trend leader in this regard, with 75% of its portfolio structured as partnership agreements.3

Still, many institutional landlords are reluctant to convert traditional leases with coworking companies into partnership agreements. Mostly because of lower predictability of the net cash flow, the risk participation—which can be significant especially during downturns—and the consequent uncertainty surrounding the negative valuation impact and tradability of those agreements.

Sales comparisons that include partnership agreements are rare, and the details of the underlying agreements are only visible to a small group of potential investors who signed confidentiality agreements during the marketing process. Furthermore, the appraisal community is constantly playing the “catch-up game” with the speed of new contracts, credit risk, and other aspects that influence the value of such arrangements.

3. CREATE-YOUR-OWN-FLEX PROVIDER

Office owners with a sizable portfolio within a market or country can create their own flex space provider under a self-run private brand. Some high-profile examples are Studio (Tishman Speyer), Flex by BXP (Boston Properties), Flex+ (Irvine Company), Space+ (Washington REIT), and Hines Squared (Hines). The potential for this model seems significant considering that Tishman Speyer, for example, estimates their flex offerings could eventually make up 20% of their office portfolio.3

When landlords create their own flexible space offerings, they don’t necessarily need to use their own brand; they can alternatively incorporate that offering into their amenity space and limit the usage to tenants within the building. Especially for larger properties like Vornado’s Penn Plaza buildings in Manhattan, these spaces provide flexibility for existing tenants during short-term expansions, contractions, and renovations.

4. EMBRACE SHORTER LEASE TERMS AND SPEC SUITES

While landlords desire secure, long-term leases and predictable cash flows that in turn promise to create a strong valuation, the trend of increased demand for flexibility has made these criteria somewhat harder—but not impossible—to achieve. As such, landlords may be enticed to embrace shorter lease terms to alleviate some of the advantages that occupiers typically seek from coworking providers. Owners can offer these shorter terms at higher net effective rents in return for flexibility.11

To reduce downtime for landlords and increase the availability speed to the occupiers, owners are also increasingly pre-building office space within their properties. These so-called spec suites further satisfy occupiers’ desires for lower capex investments while reducing tenant improvement costs for landlords via economies of scale in the buildout process. With spec suites, owners can also use a more generic, but modern fit-out design that many spec occupiers would find attractive, further reducing re-tenanting costs. With this strategy, landlords are especially aiming to recapture the decrease in direct leases with smaller tenants of 10,000 SF or less.12

However, spec suites and other aforementioned concepts directly compete with sublease availability, which has increased significantly during the pandemic. While sublease availability has started to decline, it is still at an extremely elevated level of over 20 million SF (4.4%) of Manhattan’s office inventory.19 This competition is meaningful, as the space is already built out and available in various sizes and lease duration. Even if sublease space requires a more individualized negotiation, offers a more uneven build-out quality, and a lower level of service, it can be an attractive alternative for enduses. And in certain instances, especially during a recession, the discount on the sublease rental rate could reach 30%.13

5. OWN HIGHER QUALITY BUILDINGS

In this evolved landscape, landlords must navigate various strategies based on their preference for risk exposure and operational engagement. There is no one-size-fits-all approach and every owner must decide how much exposure to internal or external coworking providers. But recent closings and market corrections in that space show that the recession risk for those business models are real, despite the early signs and the market expectation of an even stronger demand for flex offerings, once the pandemic is behind us.

The countless options and seemingly limitless offerings by various landlords and flex providers illustrate the common belief in a significant increase in demand for flexibility and also underscores the fragmentation of the market.21 Landlords are well-advised to take flex demand seriously, but their desire for long-term leases is deeply rooted in how these leases impact valuation and sale prices.

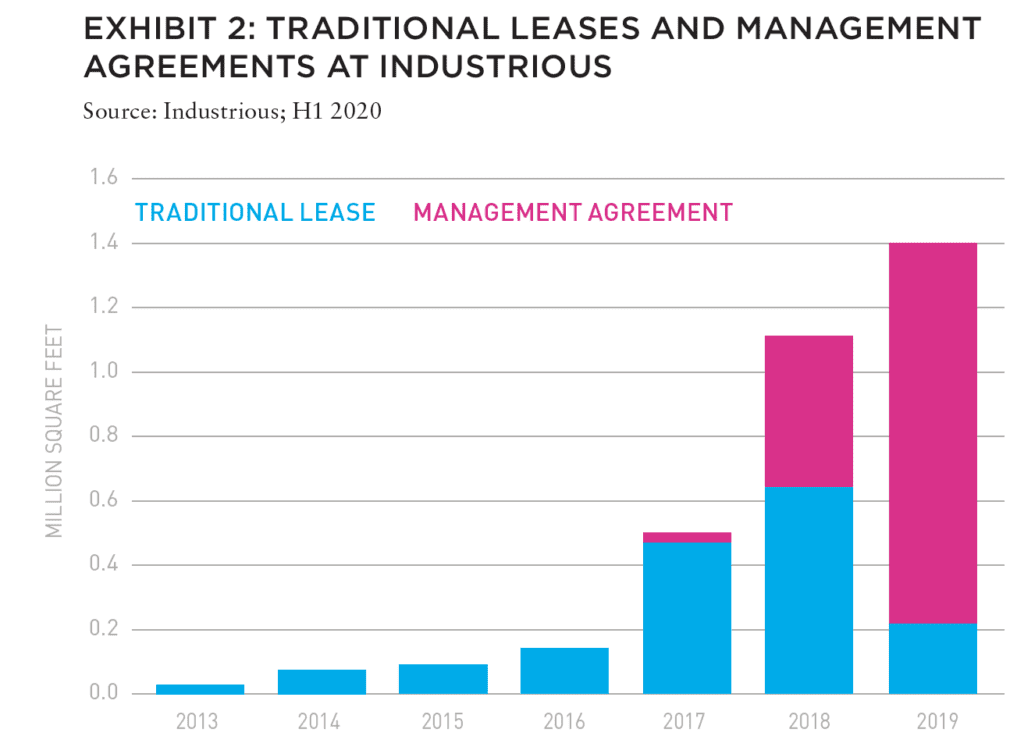

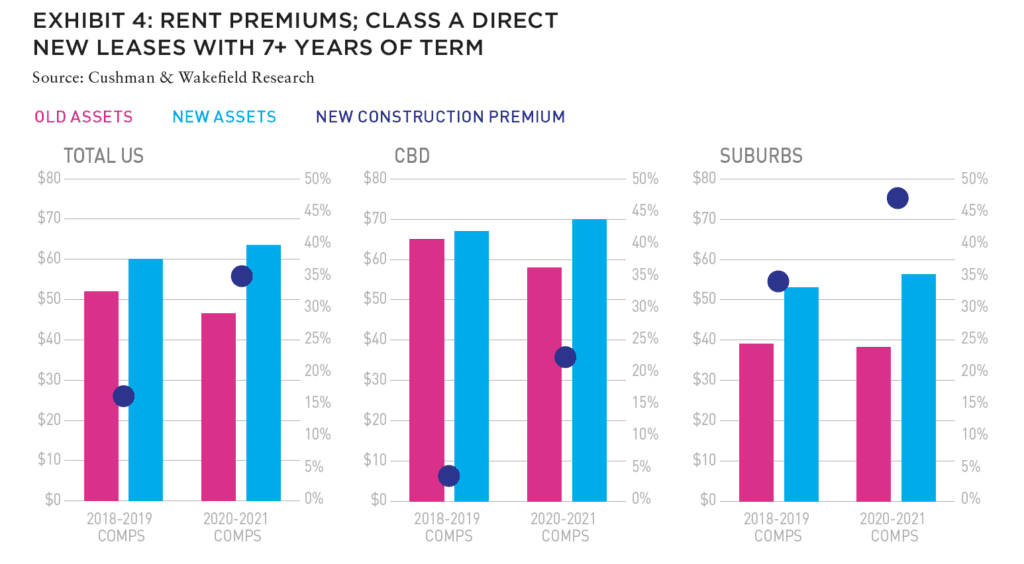

Another core defensive strategy for landlords is to focus on higher quality assets. These buildings have shown resilience by attracting desirable, strong-credit tenants with long-term leases—even during the pandemic. For example, Vornado Realty Trust, one of Manhattan’s largest owners of trophy office properties, reported an average lease term of 14.4 years for their Manhattan leasing activity in 2020—which included the fifteen-year Facebook lease at the Fairley Building and NYU’s long-term lease extension at One Park Avenue. This trend continued in 2021, where for instance SL Green continued to secure additional leasing activity during the pandemic and reached 91% occupancy for their trophy office tower One Vanderbilt – with some of the lease rates even breaking through the $200/SF barrier.14 But this trend goes beyond trophy assets. Over the last five years, CBD leasing activity in newer assets (built or renovated in 2016 or later) accounted for 25.3%, while their inventory share is just 14.4%, representing a factor of 1.7x. Additionally, these assets demanded a 35.2% rent premium over the past two years. So while older assets experienced an average rent decrease of 9.7%, newer assets generated a 4.9% rent increase.15

Additionally, these high-end assets experience higher-thanaverage rent collection, as the respective tenants generally continue their rent payments despite low physical occupancy or sublease activity.16

Overall, there is a strong business case that owning highly amenitized trophy assets in desirable locations is crucial to the health of the investment portfolio throughout the economic cycle, and even partially protects against an increased demand for flexibility.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE (FALL 2021)

NOTE FROM THE EDITOR / GROUPTHINK VS. GROUP COLLABORATION

AFIRE | Benjamin van Loon

MID-YEAR SURVEY / CHECKING THE PULSE

No matter your age or experience, 2021 has shaped up to be a year that no one can forget. Findings from the AFIRE 2021 Mid-Year Pulse Survey detail a cautious road ahead.

AFIRE | Gunnar Branson and Benjamin van Loon

CLIMATE CHANGE / REASSESSING CLIMATE RISK

The commercial real estate industry may not yet fully grasp the actual relationship between climate risk and asset pricing and value. But the knowledge is coming fast.

York University | Jim Clayton

University of Reading | Steven Devaney and Jorn Van de Wetering

Kinston University | Sarah Sayce

UNEP FI | Matthew Ulterino

NON-TRADITIONAL / THE ALLURE OF SPECIALTY SECTORS

Real estate investments have historically coalesced around common property types—but it may make sense for investors to reconsider specialty property sectors in the post-COVID world.

Invesco Real Estate | David Wertheim

NON-TRADITIONAL / NON-TRADITIONAL IS GOING MAINSTREAM

The mainstreaming of nontraditional property types is well on its way within institutional investing, which will materially broaden the real estate investment universe.

Principal Real Estate Investors | Indraneel Karlekar, PhD

DIGITAL INFRASTRUCTURE / DIVERSIFYING INTO DIGITAL

As investors look for sustainable sources of inflation-protected yield, real estate investment is increasingly blurring into a wider range of “digital” real asset investment strategies.

AECOM Capital | Warren Wachsberger, Josh Katzin, and Corbett Kruse

LIFE SCIENCES / TAPPING INTO BIOTECH

Over the past two decades, the single-family rental industry haLife sciences real estate has been a “hot” property type for the past decade—and even more since the pandemic. Will all the capital targeting the space be placed where it needs to go?

RCLCO | William Maher, Ben Maslan, and Cecilia Galliani

ESG + CLIMATE CHANGE / HIGH-WATER MARKS

Interest and excellence in ESG performance is becoming increasingly critical to portfolio strategy. So with sea levels on the rise, how can portfolios stay above water?

Barings Real Estate | Jerry Speltz

ESG + NET-ZERO / VALUING NET-ZERO

With more tenants focusing on environmental targets, the burden to reduce direct emissions places increased pressure on investors, who are at a pivotal moment in ESG strategy.

JLL | Lori Mabardi, Emily Chadwick, and Eric Enloe

ESG + FAMILY OFFICE / FAMILY OFFICES AND ESG

As sustainable investing continues to grow in popularity, family offices have taken note—and understanding ESG targets and regulations will be key for longterm performance.

Squire Patton Boggs | Kate Pennartz and Rebekah Singh

DEBT / WHY DEBT, WHY NOW?

Debt funds remain a comparatively small part of the real estate investment market, but they have been gaining in prominence in recent years.

USAA Real Estate | Karen Martinus, Mark Fitzgerald, CFA, and Will McIntosh, PhD

MIGRATION / MIGRATION IN REAL TIME

As the public health situation started to improve in early 2021 and the economy reopened, did migration flows change too—and what if we are able to answer this in real time?

Berkshire Residential Investments | Gleb Nechayev

StratoDem Analytics | Michael Clawar

URBANISM / DOWNTOWN DISRUPTION

The pandemic-driven changes to downtown areas and central business districts is changing the geography of institutional investment. What else changes because of this?

Drexel University | Bruce Katz

FBT Project Finance Advisors + Right2Win Cities | Frances Kern Mennone

WORK-FROM-HOME / CHOOSING FLEXIBILITY

Employees are increasingly demanding flexibility and choice for where (and when) they work. What strategies can landlords implement to adapt?

Union Investment Real Estate | Tal Peri

TALENT AND RECRUITMENT / TALENT PARITY

To be better prepared for future risks, firms need diverse talent. So is the goal of 50% female representation achievable in global real estate investment and asset management firms?

Sheffield Haworth | Isabel Ruiz

CLIMATE CHANGE / PREDICTING THE CLIMATE FUTURE

We are all invested in the cities, assets, and infrastructure of tomorrow, even if we might not live to see the ten largest cities in 2100. But understanding climate change can get us closer.

Climate Core Capital | Rajeev Ranade and Owen Woolcock

—

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Tal Peri is Head of US East Coast and Latin America for Union Investment Real Estate, Germany’s largest open-ended real estate fund with a global AUM of US$57 billion.

—

NOTES

1 Liz Fosslien and Mollie West Duffy, “How to Combat Zoom Fatigue,” Harvard Business Review, last modifi ed April 29, 2020, hbr.org/2020/04/how-to-combat-zoom-fatigue.

2 See also: CBRE, “Five Global Themes Influencing the Future of Office: 2021 Occupier Sentiment Survey,” CBRE, last modified February 7, 2021, cbre.com/insights/articles/the-future-of-the-office; Gensler Research Institute, “US Workplace Survey 2020,” Gensler, Accessed October 25 2021, gensler.com/gri/usworkplace-survey-2020-summer-fall; JLL, “The Impact of COVID-19 on Flexible Space,” JLL, Accessed October 25, 2021, jll.de/content/dam/jll-com/documents/pdf/ articles/covid-19-and-flexible-space-report.pdf; JLL, Global Workforce Expectations are Shifting Due to COVID-19, JLL, last modified November 17, 2020, us.jll.com/en/trends-and-insights/research/global-workforce-expectations-shifting-due-tocovid-19; Susan Lund, Anu Madgavkar, James Manyika, and Sven Smit, “What’s Next for Remote Work: An Analysis of 2,000 tasks, 800 jobs, and Nine Countries,” McKinsey Global Institute, last modified November 23, 2020, mckinsey.com/featuredinsights/future-of-work/whats-next-for-remote-work-an-analysis-of-2000-tasks-800- jobs-and-nine-countries.

3 CBRE, The End of the Beginning, CBRE, Accessed October 25, 2021, cbre.com/-/media/files/the-way-forward/the-end-of-the-beginning-north-america-flexibleoffice-market-in-2020/north-america-flex-office-2020-1.pdf.

4 “Flexible Space Solutions,” JLL Research, accessed October 25, 2021, us.jll.com/en/flexible-space.

5 Green Street, s.v. “Property Insights: The Co-Working Impact,” November 2017, greenstreet.com.

6 Newmark Group, New York City Office Market Overview, Accessed October 25, 2021, f.tlcollect.com/fr2/521/79140/4Q20_Offi ce_Market_Overview-_1.19.21.pdf.

7 Green Street, s.v. “The Co-Working Impact”

8 Christa Dilalo, Riley McMullan, Brandon Labord, and Leah Hays, “Atlanta Supply Study: Office,” Cushman and Wakefield Research, 2020, f.datasrvr.com/ fr1/820/73185/Atlanta_Supply_Study_Office_FINAL.pdf.

9 Revathi Greenwood and David Smith, “Coworking and Flexible Office Space,” Cushman and Wakefield, last modifi ed August 21, 2018, cushmanwakefield.com/en/united-states/insights/2018-coworking-report.

10 US Securities and Exchange Commission, “Form S-1 Registration Statement,” US Securities and Exchange Commission, August 14, 2019, sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1533523/000119312519220499/d781982ds1.htm.

11 Newmark, New York City Office Market Overview; Tom Acitelli, “COVID Dings the Conventional 10-Year Office Lease in Manhattan,” Commercial Observer, December 1, 2020, commercialobserver.com/2020/12/office-lease-lengths-covid/.

12 CBRE, The End of the Beginning.

13 Newmark, New York City Office Market Overview.

14 Joe Lovinger, “SL Green Asking Record $322 PSF at One Vanderbilt,” The Real Deal, July 21, 2021, therealdeal.com/2021/07/21/sl-green-asking-record-322-psf-atone-vanderbilt/.

15 Kevin Thorpe, David Smith, Andrew Phipps, Dominic Brown, Adam Jacobs, David Bitner, and Rebecca Rockey, Predicting the Return to the Office, Cushman & Wakefield, Accessed October 25, 2021, cushwake.cld.bz/Predicting-the-Return-to-the-Office.

16 “SEC Filings,” Vornado Realty Trust, Accessed October 25, 2021, investors.vno.com/sec-filings-other-reports/sec-filings/.