This article appears in Summit Journal (Summer 2020) | Download PDF

THE GLOBAL HEALTH PANDEMIC HAS TURNED OFFICE USE ON ITS HEAD—SO WHAT DOES THIS MEAN FOR THE FUTURE OF THE SECTOR?

The swift and sudden shutdowns resulting from the coronavirus pandemic have ushered in a new era of working for many office-based employees. With wide swaths of the US population working from home and no clear indication of when this period might pass, employees and employers alike have begun to question the necessity of the office for most critical business functions, with some companies, such as Twitter, making bold moves to embrace location-less/remote work styles.

For owners of office space in the US, these changes present both short- and long-term challenges. While many highly qualified individuals are focused on solving the more imminent physical challenge of how to safely welcome back occupants into the office, there has been only broad speculation of what the future of the office might look like, but very limited speculation on how to position portfolios to embrace the disruption.

In the pre-COVID-19 era, remote workers were a fast-growing, though still-small slice, of the US labor force, totaling 3.4 million full-time workers. While companies had been gradually moving towards offering greater flexibility for their workers as one of many tools in their recruitment and retention arsenal, the office has remained the focal point of business activity for many firms—until earlier this year.

Amidst the elevated health risks, major occupiers of commercial office space around the country appear to be in no rush to have their employees return to the office.

Companies such as Google and Facebook have signaled employees could stay home until 2021, and others, such as Nationwide Insurance, have opted to close all but four of its corporate offices and move toward a hybrid-remote workforce—roughly 4,000 employees strong. The perceived challenges that had for years circumvented a broader adoption of remote work (including concerns around productivity, infrastructure, communication, and collaboration) have been put to the test, to surprisingly effective results; US workers were 47% more productive in March and April than in the same two-month period in 2019.¹

While there will undoubtedly be those companies that move to a completely remote model, there will likely be many more who leverage a hybrid model. How fi rms balance this need for more space per employee and their bottom lines is poised to impact the office sector for years to come, and how investors navigate these countervailing forces will create the next cycle’s winners and losers.

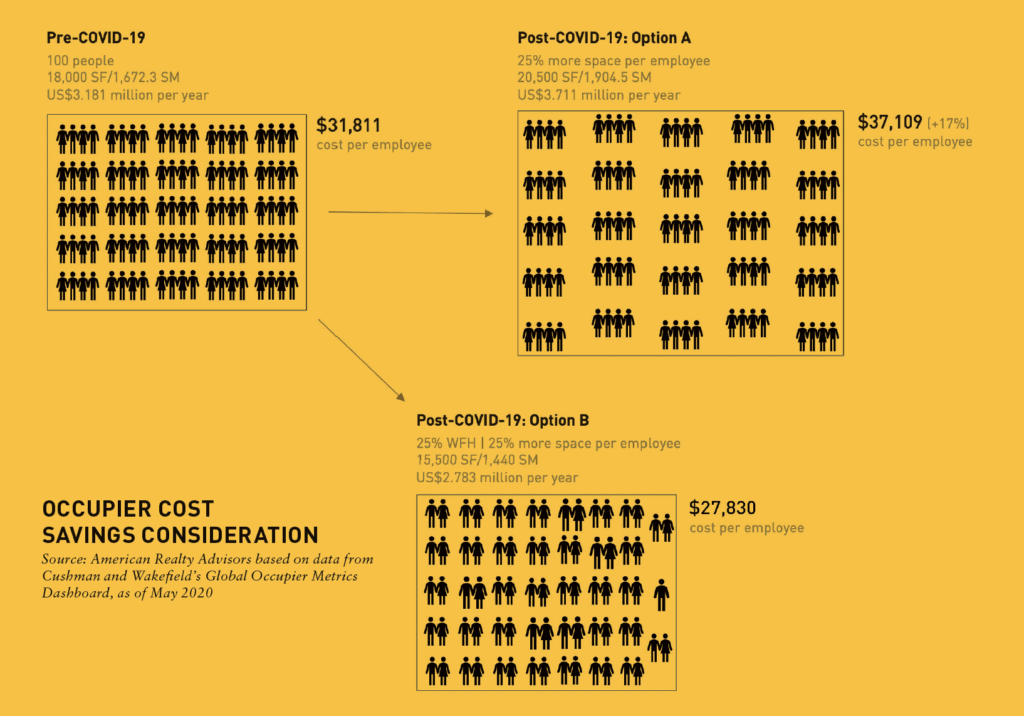

To better illustrate the impact of these choices, let us take a hypothetical company headquartered in a prime location in New York City.

Let’s assume that the lease pre-COVID-19 was executed with the notion that all 100 employees are in the office most days and there is relatively little remote mobility. With a space per dedicated desk of 125 SF/11.6 SM, the lease encompasses roughly 18,000 SF/1,672.3 SM and costs the tenant US$3.18 million annually, or US$31,811 per employee.

While this tenant and their landlord may employ superficial modifications in this interim co-COVID-19 period to gradually allow employees to return to the workplace (such as masks, temperature checks, and sanitizer stations in elevator banks, or fewer chairs in conference rooms), the return is likely to occur in phases, with at least a portion of their workforce remaining at home until the development of a vaccine or reliable therapy.

Assuming these modifications and phasing persist in some form until their lease expires, the tenant is faced with the prospect of either:

- A renewal that increases the amount of dedicated space per person by 25%, increasing the amount of space needed and annual costs by more than half a million dollars per year, or

- Allocating a certain share of workers who are expected to permanently work from home to offset de-densification.

On the surface, these two scenarios seem to offer a modest win for office landlords at best, no change at a minimum.

However, this example assumes that the company’s cost-cutting efforts are contained to the initial one-time, 25% reduction in their office-based employee count. While this may be the initial measure companies take to mitigate infection risk, it may mark the first in a series of phased transitions that could leave office occupancy considerably weakened. And these scenarios ignore the very-real possibility that some fi rms, when faced with the very real dilemma of continuing to pay rent on a space they are unable to occupy, will put their space onto the sublease market, adding downward pressure to fundamentals.

And there is evidence to suggest that firms would benefit from more fluid workforces than merely real estate cost savings. A survey of 1,200 US workers in 2019 found that employees who regularly work remotely are 22% happier than people who never work remotely, are 13% more inclined to stay in their current job for the next five years than on-site workers, and work over 40 hours per week 43% more than on-site workers do.²

Reduced or eliminated commutes, improved work-life balance, and increased productivity are oft-cited intangible benefits to employees who are given the flexibility to work remotely.

With companies focused on attracting and retaining top talent, a flexible policy that is geographically agnostic may be the new differentiator for recruitment and retention.

And that says nothing to the potential benefits of a hiring strategy that can target the best candidates from anywhere, at localized (read: lower) pay rates. Given the myriad ways in which these scenarios might pan out, an investment approach that bifurcates near- and short-term risks and opportunities by severity and likelihood is perhaps the most appropriate.

Geographic exposure to the virus and companies’ utilization and cost of space may provide some guidance. Densely populated, transit-reliant cities such as New York and San Francisco may exhibit a weakening in fundamentals first. Employers will not want to risk exposing their employees to contagion through long, crowded commutes, so may opt to extend their work-from-home periods until a vaccine is developed. The longer this dynamic exists, the more these same companies may struggle to justify paying high office rents for spaces that are not being used, which may lead to an uptick in sublease space and ultimately higher vacancy.

There is also a scenario whereby other companies (who might have already been on the fence about business costs in higher-tax coastal states) consider a physical move to a lower-cost, car-friendly metro while allowing those who wish to stay behind to continue to work remotely. This may marginally benefit office markets in places such as Texas or Florida, though these moves are also likely to reflect downsizing. Other solutions may include greater leverage of co-working facilities in suburban locales that cater to firms’ suburban employees, eliminating commute risks and lessening long-term lease commitments.

So, what can investors do today to prepare for the ensuing shift?

Follow the talent.

Companies inclined to relocate their physical operations are likely to go where those with the requisite skillsets want to live. This may mean warmer, more affordable markets in the Sun Belt with a highly educated workforce and attractive quality of life (e.g., Austin, Miami, Orlando, Tampa, Dallas, or Phoenix) may capture a greater share of office leasing. Local supply-demand dynamics need to be carefully underwritten.

Embrace flexibility.

Companies may be reluctant to commit to long-term leases when they themselves are faced with increased uncertainty. Buildings and landlords that can embrace occupiers’ needs to flex into and out of space as needs dictate with shorter-term leases or in-house co-working suites may prevail.

Differentiate product.

With the possibility of firms taking less space overall in the future, the spaces they do occupy will likely serve as physical showrooms of their culture and values. This may mean that spaces that promote environmental and workforce wellness can command a price premium over more commodity product that may fall completely out of favor and be converted to higher and better uses.

It stands to reason that the office sector is poised to undergo a dramatic transformation in the years ahead.

While we believe most companies will not forego office space entirely, the pandemic has created a permanent shift in the way companies view and support virtual work environments and just as critically, how they will use office space going forward.

Given the significant exposure to the office sector in most investors’ core portfolios, anticipating how these shifts could progress from a slow drip yesterday to a steady stream today can help mitigate against downside surprises tomorrow.

—

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Stanley Iezman is Chairman and CEO and Sabrina Unger is Managing Director, Head of Research and Strategy, for American Realty Advisors, one of the largest privately held real estate investment management firms in the US.

NOTES

1. Results based on analysis of 100 million data points from 30,000 Americans by Prodoscore, a leader in employee visibility software. See: Prodoscore, “Prodoscore Research from March/ April 2020: Productivity Has Increased, Led by Remote Workers,” BusinessWire (May 19, 2020): businesswire.com/news/home/20200519005295/ en/Prodoscore-Research-MarchApril-2020- Productivity-Increased-Led

2. Owl Labs, “State of Remote Work 2019,” Owl Labs (September 2019): owllabs.com/state-of-remote-work/ 2019

—