INSIGHTS FROM THE AFIRE TAX & REGULATORY SUMMIT

The global real estate investment industry is highly dependent upon the vacillations and nuances of tax and regulatory issues to determine portfolio decisions, partnerships, and investment theses. Integral to AFIRE’s member mission of becoming better investors, leaders, and global citizens is the need to create a space for experts to convene and discuss pressing questions that not only affect their own work, but ultimately, the success of their clients and their investments.

The specialized expertise needed for building long-term investment strategies, especially across borders, is often proprietary and can only be developed through exclusive access. However, as much as real estate investing is a competitive industry, its overall influence thrives on shared knowledge, expertise, and the ability to translate industry arcana into actionable intelligence, policy development, and risk management—especially in the face of mounting global economic and political uncertainties, technological advancement, and climate change.

With these notions of change as a backdrop, AFIRE’s recent inaugural Tax and Regulatory Summit invited both members and guests involved in navigating tax and regulatory issues to address the latest ideas (and questions) related to Opportunity Zones (OZs), Qualified Foreign Pension Funds (QFPFs), the Foreign Investment in Real Property Act (FIRPTA), treaty changes, debt investing, blocker planning, and other topics of pressing interest for both US and non-US real estate investors.

While experts around the room provided privileged updates on these and other issues, the critical question throughout the day focused on where we are now, and what new laws, policies, practices, and agreements might bring us in the future.

For example, much of the discussions looked at the implications of FIRPTA. When it was first introduced in 1980, FIRPTA imposed taxes on gains realized when non-US individuals or corporations disposed of US real property interests by treating those gains similar to what the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) considers “effectively connected income,” so generated when a non-US individual or corporation otherwise engages in a trade or business in the US.

FIRPTA has proven a challenge for many non-US investors in real estate over the past decades, even as Congress has tacked on new amendments and proposed regulations over the years as a way to alleviate questions or complications resulting from the act. Most recently, in mid-2019, the IRS and the US Treasury proposed regulations that would provide an exemption from the FIRPTA tax for QFPFs, which gave some investors supposed relief from the regulations—until they started to dive deeper into the language of those regulations. Specifically, how are the regulations actually defining “pension fund?”

The answer isn’t so straightforward, and thus, the relief was temporary.

“We can all agree that the proposed regulations are friendly overall, but they don’t yet have a cohesive definition of “pension or retirement benefits,” said David Friedline, Partner at Deloitte Tax LLP. “Not all pension funds worldwide are created equal. It doesn’t appear Congress’ intention is to require foreign pension funds to be fundamentally similar to US pension funds, so there may still be work to be done to clarify the qualification of certain types of pensions that differ from ours.”

One of the ways non-US investors have worked through FIRPTA has been to explore differing fund structures and vehicles—some more complex than others. “Instead of simpler structures, we’re instead seeing an increasingly wide range —REITs, 892, QFPF, US tax exempt,” said Dene Dobensky, Principal at KPMG LLP. “Though there is a range of vehicle choices, they often make for more cost, more risk, and frequently, they require more rebalancing.”

As an extension of this trend towards rebalancing, some investors have expanded their interests in the Opportunity Zone (OZ) program, which was created by the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) to spur economic development and job creation in distressed communities by providing tax benefits to investors who invest eligible capital into these communities (approximately 8,700 in the US and Puerto Rico). Seemingly straightforward, significant time has been spent by the tax and regulatory community determining what actually qualifies as eligible capital.

As a crucial qualifier on the definition of the program —that it’s not merely an easy way for investors to qualify for tax benefits—Eric Requenez, Partner at Stroock & Stroock & Lavan LLP, said, “An opportunity zone does not turn a bad deal into a good one. You still need to have a good deal, and that’s why it’s important for investors to understand the Opportunity Zone program—including the requirements that may impact their investments.

While the benefits of the OZ program can be divided into three primary benefits—tax deferral, tax reduction, and tax elimination—each are subject to varied and evolving nuances, not only with the OZ program proper, but the countries where investment capital originates. Foreign investors can generally invest and trade in non-originated US real estate loan securities without any US income or withholding tax consequences, though beneficial treatment is subject to the various requirements of the trading safe harbor, the portfolio interest exception, or an income tax treaty.

In contrast, non-US-based investors who operate a trade or business (or where an income tax treaty applies, investors who have a “permanent establishment”) in the US are subject to US tax on their net income that is “effectively connected” to that business. And if these investors originate loans directly, they may be considered to have a trade or business (or permanent establishment) in the US and may be therefore be subject to US federal and state income tax, branch profits tax, as well as tax filing requirements.

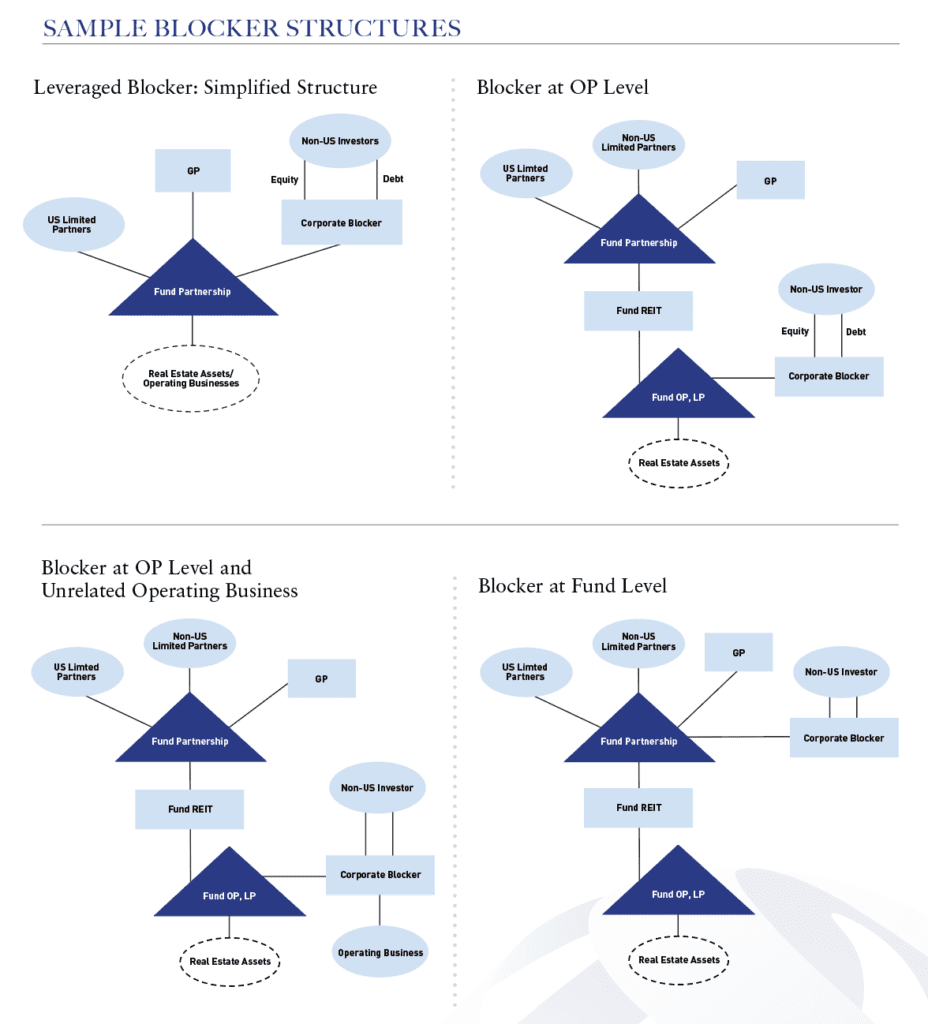

To solve for these taxation issues, blockers serve as a standard feature of inbound investment structures, especially in private equity and real estate, and is treated as a corporation for US federal tax purposes and pays tax in the US at the applicable corporate rate (currently 21%). Typically, such structures are intended to insulate foreign investors from US federal tax filing requirements and reduce the effective tax burden on investors by reducing corporate taxable income through the use of deductible interest expense.

Blocker structures vary in composition and distribution over time, and there is no one-size-fits-all solution for real estate investors. As one example, while REITs are used under certain circumstances to avoid FIRPTA issues, they also have the potential to entail high compliance costs as well as a 30% withholding tax on dividends. Alternately, treaty qualification is much easier for C corporation dividends—in most cases 15% or lower. Where the C corporation tax can be reduced through leverage, and portfolio interest exemption can be satisfied, the leveraged blocker will often be preferable to a REIT.

In the midst of these and other approaches to blocker structures, according to Jonathan Talansky, Partner at King & Spalding, the proposed regulations under the new section 163(j) of the TCJA have answered some questions but generated new ones in their place. For example, the proposed regulations contain a safe harbor for equity REITs, such that if a REIT holds real estate directly or through partnerships or other REITs, it will be eligible to make the real property election. This applies to all of the assets of the REIT as long as 10% or less of those assets consist of mortgages and other real estate financing assets, though it remains unclear how this safe harbor applies to certain tiered structures.

For many at the Tax & Regulatory Summit, such nuances underscore the need and value of conversation across the industry, and ultimately invoke the archetype of the one-armed tax expert. Because few answers or opinions are straightforward in the world of real estate tax and regulatory issues, the industry calls for a legion of one-armed attorneys and accountants, because to any question, their best answer will (and perhaps should) be, “Well, on the one hand…”

In many cases, multi-billion-dollar investments hinge on how experts interpret complex legal and regulatory minutiae, which cannot (and should not) be interpreted or applied in a vacuum. Success in real estate investing means learning from others and having the ability to connect with peers facing similar issues. The AFIRE Tax & Regulatory Summit, even in its inaugural state, has not only created this rarefied forum, but also provides a rich basis for ongoing discussions affecting the future of our work around the world.

—

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Benjamin van Loon joined as AFIRE’s first Communications Director in 2019, responsible for strategy, innovation, technical operations, communications, and thought leadership, including serving as editor-in-chief of Summit Journal.

THIS ARTICLE ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN SUMMIT (SPRING 2020)

—