A data-driven initiative to remake how and what we build.

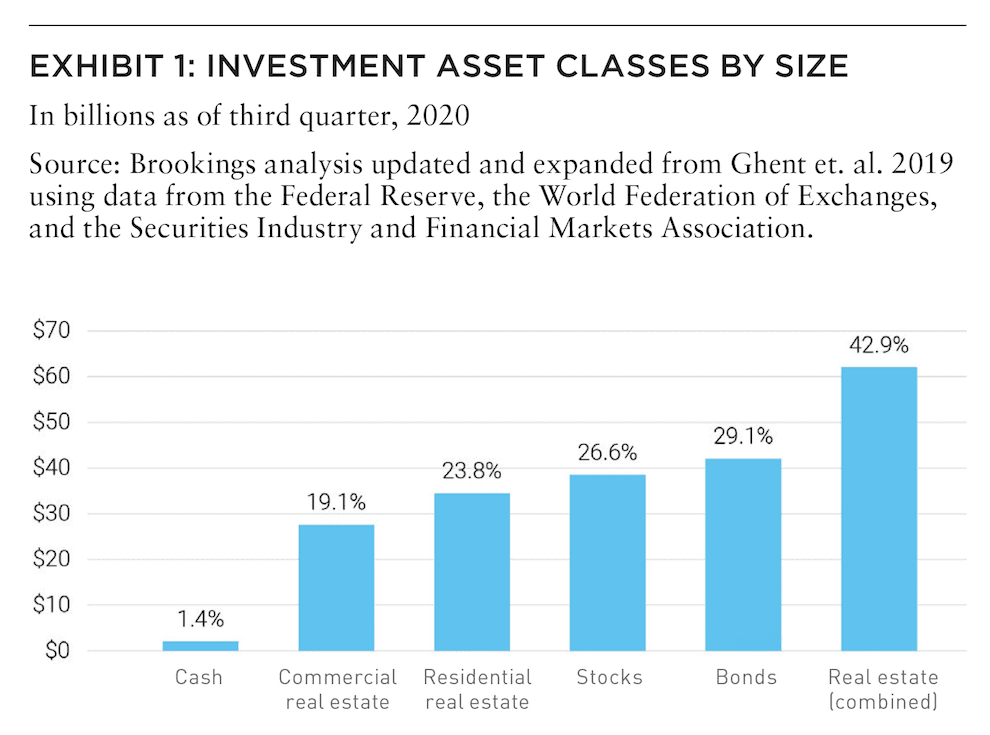

Real estate plays a defining role in the American economy. It is by far the largest asset class in the United States, comprising over 40% of private assets nationally, followed by bonds, stocks, and cash (Exhibit 1). But we invest—and reap—far more than wealth from what we build. Our built environment is an expression of health, innovation, community, and culture. It is a physical reflection and embodiment of the human experience, its values, and its aspirations—and the ways they have evolved over time, for better and for worse.

Real estate is cyclical. Industry players are accustomed to periodic market resets, where credit tightens, demand is weak, and the construction sector sheds jobs. During these “resets,” some combination of time, bailouts, and corporate pivots ushers in the next cycle of growth. The current cycle began with a reset triggered by the subprime mortgage lending crisis and subsequent Great Recession of 2007 to 2009. Today, the industry is overdue for its next reset—but this one is different.

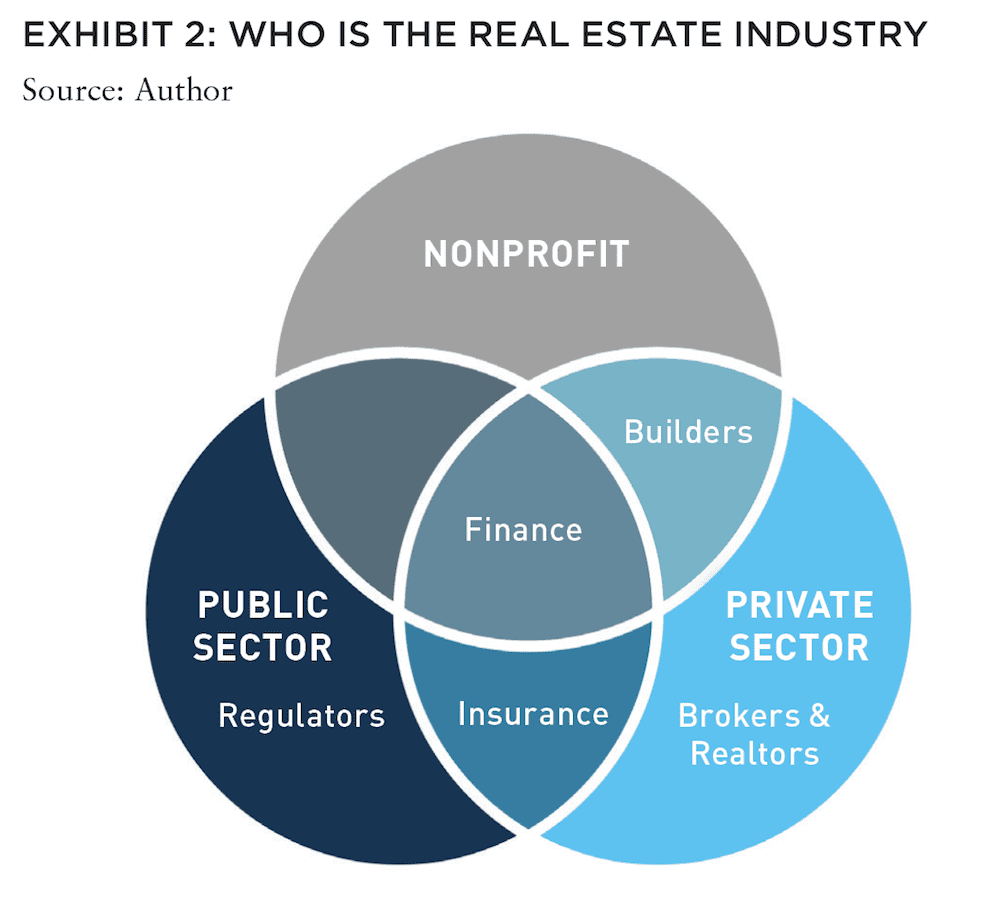

For generations, the presumptive American real estate consumer has been a middle-class White family—a fact that is reflected in the products, pricing, planning, and public policies that form the baseline of industry practice. But today, five converging trends are disrupting this market fundamental: persistent segregation by race and income, the demographic transformation of America, destabilized regional housing markets, the future of work, and disruptions to the retail ecosystem. Thus far, the real estate industry has only responded at the margins to these trends. If we continue “business as usual,” the real estate industry risks not only another market crash, but also becoming a central contributor to the deterioration of American political and social cohesion.

The intersecting crises of 2020— the COVID-19 pandemic, subsequent economic recession, racist police brutality, and climate-induced catastrophe— are exposing and accelerating economic and fiscal fragility, environmental vulnerability, and deep inequities that have been mounting for decades. These crises were born in no minor part out of land use and investment patterns—heavily influenced by discriminatory policies, industry practice, and toxic cultural attitudes— which prioritized profits over stewardship of the asset class that comprises the building blocks of our economy and society.

Yet these crises are occurring at a time when the demand for communities that are more prosperous, resilient, and equitable is on the rise. For years, anger over persistent racial and economic segregation and disinvestment, demographic shifts, and changes in where and how we work and shop have been shifting both needs and preferences for housing, retail, and office space—not only in terms of what gets built, but also where and how buildings cluster and connect with one another in place.

But despite mounting signs and evidence, the real estate industry—from local developers to Wall Street financiers—has remained structurally unprepared to meet this demand. Instead, the industry has remained deeply entrenched in or beholden to financial, legal, and professional institutional frameworks that pick winners and losers—to the detriment of the greater American society. This, in turn, has left too many communities one Hurricane Katrina (climate crisis) or one global pandemic (COVID-19) away from economic disruption and fiscal deterioration, hampering their collective ability to fully recover and making them all the more vulnerable to future calamities.

All this provides both an imperative and an opportunity for the real estate industry— supported by policymakers— to reimagine our built environment and reset current policy and practice toward that vision. To this end, these leaders must recognize the need to create more “communities of opportunity”—with full appreciation of the fiscal, social, and environmental benefits that doing so will yield for cities and regions. More than that, they need to embrace their role and responsibility in shaping that future.

WHAT ARE “COMMUNITIES OF OPPORTUNITY”?

“Opportunity Communities” are a model developed by the Kirwan Institute at the Ohio State University, which have been mapped in multiple US regions through a partnership with Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) Sustainable Communities Initiative under the Obama administration. The model is holistic and flexible to local values regarding what matters most and how to measure what makes a neighborhood a great place to live, but the core concept is that communities of opportunity are places that have decent housing that most people can afford; have proximity to jobs; are multimodal, meaning walkable and transit-accessible; have quality public schools; and are healthy and resilient, with green space, access to food, and manageable disaster vulnerability.

THE GREAT REAL ESTATE RESET INITIATIVE

This initiative presents and describes the major forces that have pushed the industry toward this moment, and then will seek to articulate the practices and policies the industry and the public sector must adopt in order to successfully meet it.

We begin by describing five sets of structural market trends, and why they matter to our collective ability to create more prosperous, equitable, and resilient communities of opportunity. We will then kick off a collaborative effort to develop a “Real Estate Reset” playbook with partners inside and outside the industry, featuring a yearlong multimedia series that will articulate specific, actionable ideas for policy and practice reform.

- Separate and unequal: Persistent residential segregation is sustaining racial and economic injustice in the US.

- Modernizing family: America’s demographics are transforming, but our housing supply is not.

- Risky (housing) business: Distorted and destabilized housing markets are pushing households into climate-risky, low-opportunity communities.

- The office, reimagined: The nature of office work is shifting, and so must downtowns.

- Retail revolution: The new rules of retail call for small business empowerment.

The goal of this joint Brookings-LOCUS initiative is to facilitate a more transparent and inclusive conversation in real estate that goes beyond talking to each other behind tiers of member-only paywalls. Through these discussions, it is our hope to present a new vision for industry practice that looks further than short-term gains or what’s hot for the next quarter, and instead sets in motion a systemic transformation of the real estate ecosystem— one based on care and common sense consideration of our assets to nurture better outcomes for more people and places.

ALSO IN SUMMIT (SPRING 2021)

GREAT LAKES / Tightening the Belts: How are shorthand labels like the “Sun Belt” and the “Rust Belt” shaping investment decisions? Should they?

AFIRE | Gunnar Branson and Benjamin van Loon

SOCIAL ISSUES / The Great Real Estate Reset: A data-driven initiative to remake how and what we build.

Brookings | Christopher Coes, Jennifer S. Vey, and Tracy Hadden Loh

SOCIAL ISSUES / Confronting the Myth: The events of the past year have driven businesses to confront racial inequity, but some still shy away from the challenges needed to make real progress.

Alfred Dewitt Ard Consulting | Shumeca Pickett

INDUSTRY OUTLOOK / CRE Prospects Post-COVID-19: How is commercial real estate set to perform in the post-COVID world?

Aegon Asset Management | Martha Peyton

HOSPITALITY / Time to Check In: If history is a guide, the time to invest in hotels is when things look bleak. This appears to be one of those times.

Barings Real Estate | Jim O’Shaughnessy

HOSPITALITY / Hoteling 2.0: The pandemic has impacted the hospitality, but a growing wave of non-traditional investors has shown heightened interest in the evolving industry.

JLL Hotels & Hospitality Group | Gilda Perez-Alvarado

RESIDENTIAL / Safe as Houses?: The future of residential investments is all about demographics—and the forces behind them.

American Realty Advisors | Sabrina Unger

RESIDENTIAL / Housing for Goldilocks : The pandemic highlights the advantages of single-family and appears to have accelerated migration to less dense, more affordable areas.

GTIS | Eliot Heher and Robert Sun

DATA CENTERS / Data Centers, Stage Center: Data center investments have proven resilient in periods of volatility—and they’re only going to become more essential and important into the future.

Principal Real Estate Investors | Bob Wobschall

CLIMATE CHANGE (WHITE PAPER) / Rather Than the Flood: A comprehensive look at climate-induced water disasters and their potential impact on CRE in the US.

New York Life Real Estate Investors | Stewart Rubin and Dakota Firenze

LOGISTICS / Reforging the Supply Chain: The only way to deliver on the service promises of a booming logistics sector requires a complete reimagination of the supply chain.

Stockbridge | David Egan

DEBT AND LEVERAGE / Leveraging Control: Though leverage is an important part of capital funding, it’s important to ask LPs if (and how) they should take control of their real estate leverage.

RCLCO Fund Advisors | William Maher and Ben Maslan

DEVELOPMENT / Recasting Risk and Return: The investment community can have an active role in economic recovery—but it will require recasting the traditional risk/return framework.

Standard REI | Shubrhra Jha

CORPORATE TRANSPARENCY ACT / Transparency Rules: Non-US-based investors face the disclosure regime of the Corporate Transparency Act. What do you need to know?

Pillsbury | Andrew Weiner

PENSIONS (WHITE PAPER) / Rising Pressures: The latest joint, in-depth report from Praedium and SitusAMC looks at rising fiscal pressures on state and local governments.

Praedium Group and SitusAMC Insights | Russell Appel, Peter Muoio, and Cory Loviglio | SitusAMC Insights

TALENT AND HR / Plugging the Skills Gap: Several trends are forcing change in the global commercial real estate industry, driving demand for new skills. How is the industry responding?

Sheffield Haworth | Max Shepherd

ESG / Operationalizing the Sustainability Agenda: During a time of unprecedented disruption, how should businesses approach the “new metrics” ESG of performance?

AccountAbility | Sunil A. Misser

Very few Americans live in neighborhoods that are affordable, green, close to jobs, and racially and economically integrated— to the point where it is a relatively common view that such communities are an idealistic or utopian vision rather than an achievable goal or national necessity. While most Americans agree that our economic system favors the powerful, there is no broad consensus from the White majority that integration is essential to make our country more fair. Racial integration without economic integration—also known as gentrification—has consumed the urbanist movement with controversy.

A mountain of research and a world of common sense tell us that place matters. There are so many essentials to the American dream that are geographically constrained, and the only way to ensure that Americans of all races and incomes have a fair opportunity is to build a world where good neighborhoods are not scarce, expensive, and exclusive, and where all households can put down roots and keep them. The attributes of communities of opportunity—good schools, proximate jobs, retail amenities, and parks—are tied to place. We need more good places for more people.

Today, well over half a century since the civil rights movement fought for the principle that separate is inherently unequal, real estate industry practices and local public policies have not been held accountable for making very little progress on integrating our neighborhoods. If we want to see progress on inclusion and racial justice, the industry and policymakers will have to work together to dismantle these systems and replace them with ones that nurture opportunity and connection.

THE TRENDS

Generations of economic and demographic shifts—facilitated by public policy—have produced a hyper-segregated metropolitan landscape, enabling predatory lending structures in and devaluation of minority neighborhoods.

- Federally subsidized suburbs created generational wealth-building opportunities for White people.

After World War II, loans guaranteed by the Federal Housing Administration and the Department of Veterans Affairs opened up the possibility of homeownership (and wealth-building) to millions of American households. However, these loan programs were explicitly structured to exclude Black people and to favor particular places: the newly minted suburbs.

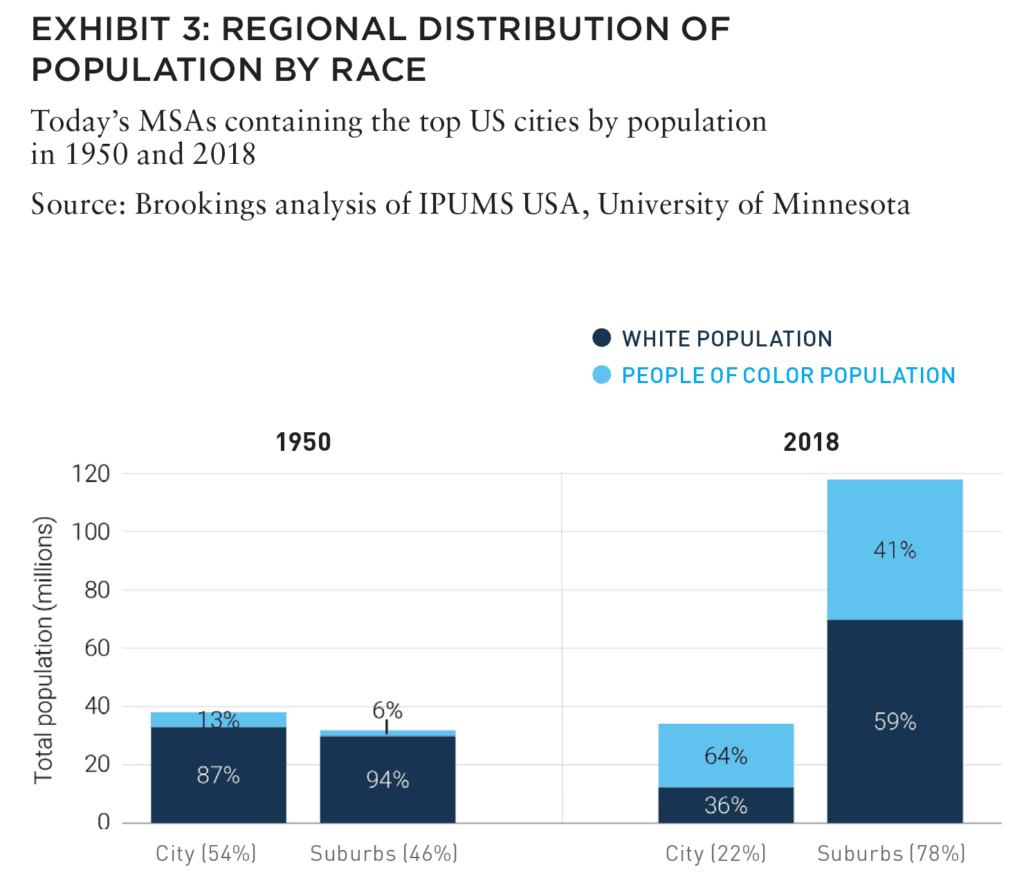

In 1950, the 50 largest US metro areas contained almost half of the country’s population. These areas in aggregate were 90% White in that year (matching the nation as a whole), but the suburbs were even Whiter, at 94%. As the civil rights movement opened up the prospect of integration, White flight to the suburbs only intensified, significantly increasing the spatial scale of racial segregation. Jurisdictional boundaries reinforced this segregation: Even as Black and immigrant populations began to move into suburban areas, they encountered the same exclusionary and segregationist zoning policies that created segregated cities and the first White suburbs years prior. The upshot of all this is that today, the vast majority of White people live in suburbs—and White people and people of color largely do not live in the same suburbs.

From 1950 to 2018, the United States went from 90% White to 60% White. The US has been becoming more multiracial rapidly in recent decades, with the total population of people of color increasing by 51% between 2000 and 2018, compared to a 1% increase in the White population.

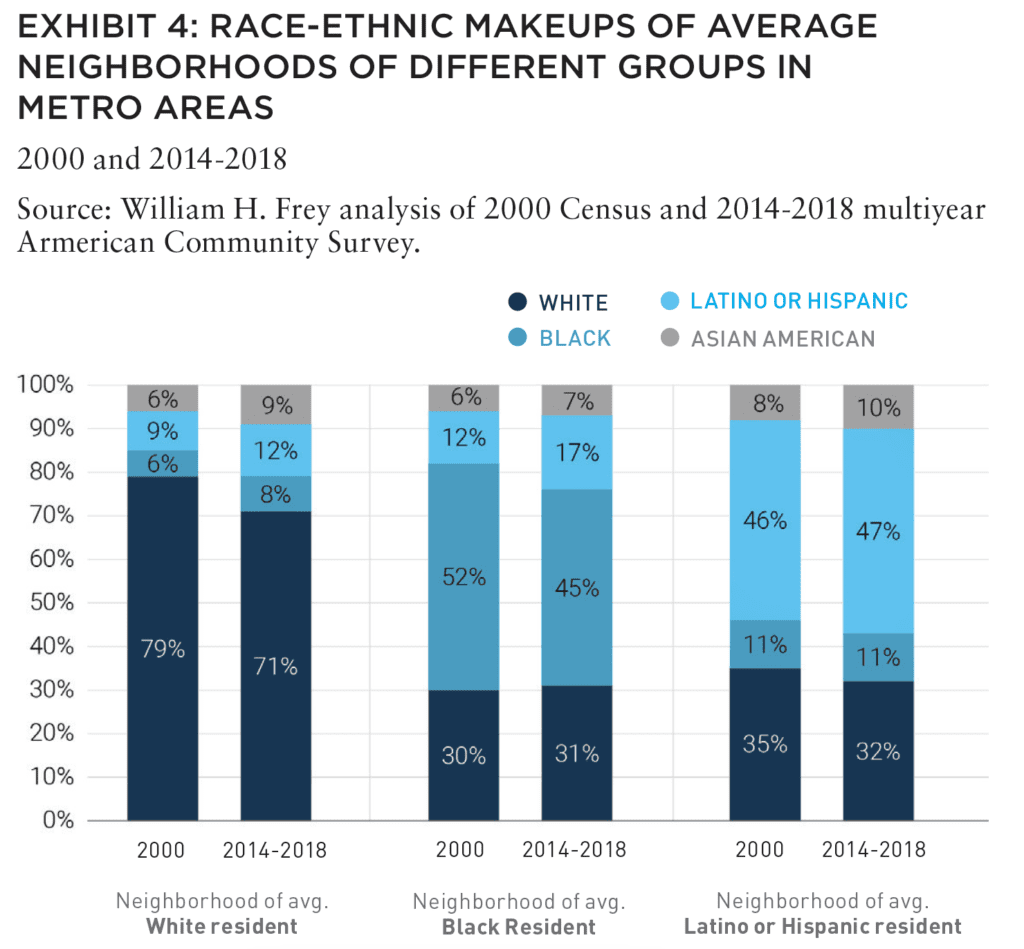

All this change has yielded some progress on racial integration. As Exhibit 4 shows, the neighborhood of an average White resident in the 100 largest metropolitan areas became slightly less White between 2000 and 2018, decreasing from 79% White to 71%. More notably during this period, the neighborhood of the average Black resident crossed the threshold from majority-Black to a diverse plurality because of Latino or Hispanic population growth. Still, while our cities and regions are becoming far more racially and ethnically diverse, segregation has remained persistent.

- Suburbanization has also segregated the nation’s neighborhoods by income.

By enormously expanding the footprint of the American metropolitan settlement, suburbanization created a patchwork of communities built by design to be spatially sorted by income. Both modern zoning and the scale of modern housing industry production have channeled a century of growth into different types of housing rigidly segregated in space. Growth at the subdivision scale, instead of by parcel or by block, created and catapulted to dominance an unprecedented urban form: communities where detached single-family homes do not share a property line or road access with anything but other single-family homes. Thus, those who can afford those homes do not see or share space with households outside their real estate market bracket. The allocation of low-income housing tax credits, housing vouchers, and the siting of public housing also contribute to today’s unprecedented isolation of low-income people of color.

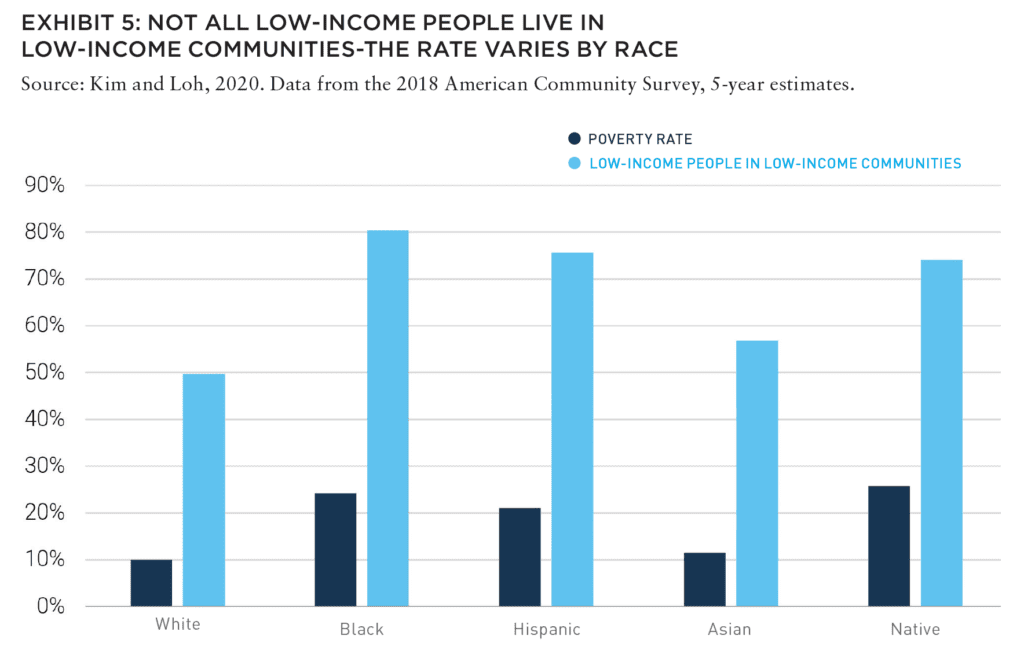

Nationwide, over 80% of low-income Black people and three-quarters of low-income Latino or Hispanic people live in communities that meet the federal statutory definition for “low-income” communities. This is in contrast to just under half of low-income White people. These patterns have long been evident in center cities, fueling tremendous political tension between a small number of very wealthy, mostly White neighborhoods and low-income communities of color with their own needs and priorities. But such patterns are repeating themselves in suburbs, too, with the increasing concentration and isolation of low-income residents now the most common form of neighborhood change in these jurisdictions as well.

- Segregation enables the real estate finance industry’s predatory targeting of Black and Brown neighborhoods.

The real estate finance industry has consistently exploited and exacerbated segregation since World War II, beginning with excluding Black neighborhoods from eligibility for homeownership or rehabilitation loans—a practice known as redlining. And throughout the civil rights era, the industry exploited, reinforced, and worsened segregation through other racist lending practices.

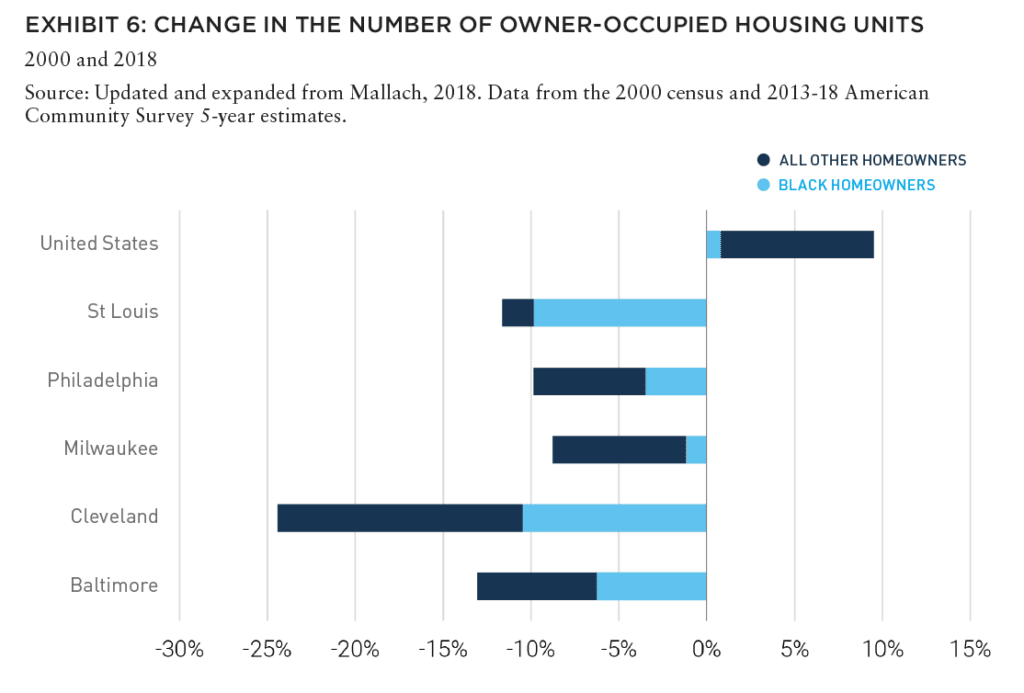

Most recently, there is widespread evidence that the real estate fi nance industry targeted Black and Latino or Hispanic neighborhoods with subprime loan products, committing “reverse redlining” in the years leading up to the 2008 financial crisis. As a result, foreclosure rates between 2005 and 2009 were an estimated 3.5 times higher in Black neighborhoods than in White neighborhoods, and 2.7 times higher in Latino or Hispanic neighborhoods. The cumulative outcome of decades of predatory lending practices—in combination with other economic trends— is a dramatic erosion of homeownership, concentrated in “middle neighborhoods” and legacy cities (Figure 4).

Suburbanization, particularly in slow-growth regions, has had a destabilizing effect on housing values in predominantly Black neighborhoods. But undervaluation is not only a function of low demand. Rather, systemic bias in lending and appraisals are among the reasons that Black neighborhoods are significantly devalued relative to predominantly White neighborhoods. Analysis by Andre M. Perry, Jonathan Rothwell, and David Harshbarger revealed that after controlling for differences in housing quality and various neighborhood characteristics, homes in majorityBlack neighborhoods were valued 23% lower than homes in neighborhoods with few or no Black residents.

WHY THESE TRENDS MATTER

Public policy and industry practice have produced a separate and unequal landscape of American neighborhoods, propagating multigenerational negative impacts on health, social mobility, and wealth for people of color as well as harmful divisions in our economy and society.

These systemic inequities have most recently been exposed by COVID-19’s disparate impacts along lines of race and ethnicity. Nationwide, Black people are dying at 2.4 times the rate of White people—the result of the inequitable living conditions, work circumstances, underlying conditions, and lower access to health care that characterize segregated neighborhoods.

But the impacts of segregation extend much further than COVID-19. Segregation has made it possible to geographically target—as well as withhold resources from— minority communities through a host of negative policies and practices, including overpolicing, underinvestment, and devaluation. These are forces that impede wealth accumulation and halt social mobility. As of 2016, the median net worth among White families was 10 times that of Black families, and more than eight times that of Latino or Hispanic families.

These racial wealth differences are not simply due to familial or inheritable differences—they are the result of a community context with worse access to education, employment opportunities, health care, and open space. For example, Black students are seven times more likely than White students to attend high-poverty schools with a high share of students of color, which have been consistently linked to lower academic achievement levels. Black urban neighborhoods are literally hotter, sometimes by 10 degrees Fahrenheit or more. And Black entrepreneurs—including those in real estate— have less access to capital (such as the Paycheck Protection Program) in part due to racial prejudice and ongoing redlining by business lenders and the appraisal industry. Because of that, Black small businesses owners are more likely than their White counterparts to use personal savings and finances (including home equity) to start businesses—repeating segregation’s loop of exclusion and discrimination, where Black people face barriers to homeownership and wealth-building in communities of opportunity.

Beyond the direct effects on individuals and families, race and income-based segregation has long-term, negative impacts that affect all residents of a community. A 2017 report from the Urban Institute and Chicago’s Metropolitan Planning Council found that higher levels of racial segregation are associated not only with lower income levels for Black people, but also lower educational attainment for both White and Black people, as well as lower levels of public safety for all residents of an area. Similarly, Perry and his colleagues document a $156 billion cumulative loss from the devaluation of homes in Black neighborhoods—money that would otherwise be circulating in local economies. As law professor Sheryll Cashin observed, this “segregation tax” is also costly to White people, who pay extreme price premiums to live in exclusive neighborhoods. McKinsey & Company estimates that continued racial and economic segregation will cost the US 4% to 6% of its GDP by 2028 due to its dampening effect on consumption and investment.

Whatever the calculations, policymakers and industry leaders need to take heed of these impacts and use their power to divest from the exploitation and exclusion of communities of color. Instead, they should actively invest in new policies and practices that will advance connection, integration, and prosperity for Black and Brown people and places.

—

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Tracey Hadden Loh is a Fellow and Jennifery Vey is a Senior Fellow for the Anne T. and Robert M. Bass Center for Transformative Placemaking at the Brookings Institution. Christopher Coes is a Nonresident Senior Fellow in the Metropolitan Policy Program at the Brookings Institution.

—