For the past several years, real estate industry watchers have hailed insurance costs as the canary in the coal mines of climate change. With global temperatures continuing to rise at a geologically unprecedented pace, the canary remains in flight. But rather than asking when it will land, it may be better to start planning for its eventual escape.

Within the world of architecture and engineering, the nomenclature of “climate-responsive” design is well established and built on centuries-old precedent, especially in areas of the world demanding design adaptation in the face of otherwise “typical” climate extremes.1 And yet in other regions that have seemingly stable and predictable weather patterns—at least within human memory—the need for climate-responsive approaches have fallen lower on the scale of importance for development and investment.

For example, some of the greatest environmental challenges historically faced by Los Angeles, the second-largest city in the US, include earthquakes and drought effects. And the city has developed accordingly, extending its trademark mix of suburban sprawl, pockets of urban density, and religious subservience to car culture. Its Mediterranean climate and generally stable weather patterns have helped it secure its place on the global network of cities, and its engineers, architects, and investors have developed the city over the past century according to this dogma.

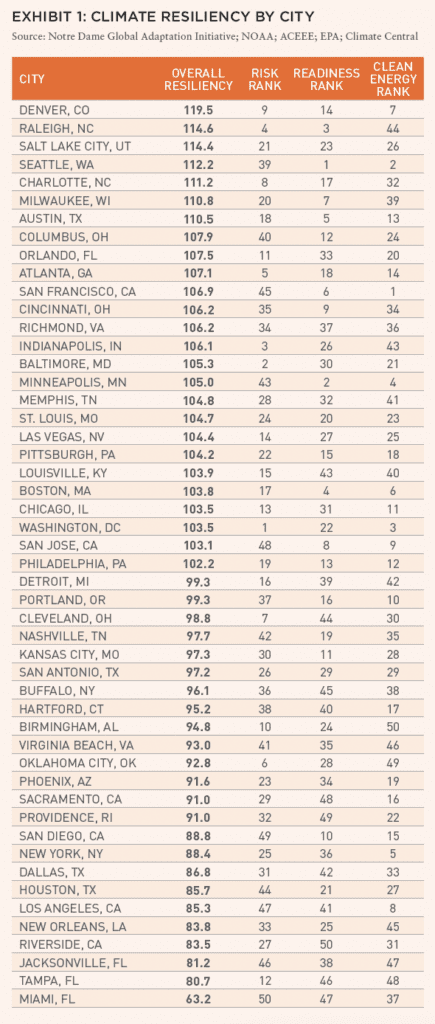

But climate resilience for modern cities such as Los Angeles is necessarily unorthodox, and today demands what the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (in collaboration with the NOAA, ACEEE, and EPA) defines as actual resilience, measured by both “risk readiness” and clean energy reliance.2 With these elements as leading criteria for determining resilience, Los Angeles is ranked one of the least climate-resilient cities in the US, just ahead of New Orleans, Louisiana; Riverside, California; and Jacksonville, Tampa, and Miami in Florida (see Exhibit 1).

In other words, in their current states, Los Angeles and the other US cities at the bottom of this list are the result of an urban design that eschewed the priority of climate-responsive design, particularly because the extra costs and the benefits of such development didn’t make financial sense in the era of America’s nascence and twentieth-century expansion projects.

Patient investors may have operated on decades-long horizons in these growth years, but few—if any—were able to forecast or financially calculate for the spikes in global temperature (and related weather symptoms) we’re now experiencing. The current cultural and corporate “climate reckoning,” where even major institutional players are now competing for best-in-class climate responses, is ultimately the result of this decades-long ambition—or myopia.

Nonetheless, this reckoning has produced some innovative and future-focused solutions that are also proving to be financially viable. For example, a recent case study from the Urban Land Institute demonstrates that even in climate-threatened south Florida, there is the possibility to invest in climate-responsive building infrastructure and services—and remain profitable.3

The case study outlines a luxury Florida resort, valued at more than $500 million, within an institutional real estate portfolio. Like most building in south Florida, the building was designed to withstand Category 3 hurricanes, including predicted storm surges of up to sixteen feet. The lowest occupied floors of the resort were twenty feet above the building’s baseline elevation, but its infrastructure systems were sitting at nine feet, putting the entire building at risk.

After acquiring the asset and noting these gaps in resilience strategies, the owner made several infrastructural and architectural changes to the building, including relocating its entire electrical infrastructure above the twenty-foot mark, despite the fact that code only required twelve-and-a-half feet. They also added five emergency generators to the property, an underground fuel tank to power those generators for up to ten days, and other fortifications and protections.

Despite the cost of these upgrades and added protections, “the owner estimates that its resilience investments boosted the insurable value of the property by 50 percent”—all while lowering its annual insurance premiums by an estimated $500,000. And the added benefits of the various building upgrades have also been estimated to save the building around $110,000 per year in energy costs, and up to $75,000 per year in water usage and irrigation costs.

While this case study provides a strong example of how an asset can guard against climate risk and remain insurable, it’s likewise an example of a building guarding itself against a wider infrastructural shortcoming that will necessarily need to be addressed by both public entities and private investors. According to the Milken Institute Innovative Finance team, the US alone is facing around $10 trillion in climate-resilient infrastructure needs by 2050.4

Correcting this shortcoming will be an uphill battle, as the Climate Policy Initiative—which has developed a proprietary tool to track investment performance for climate-resilient infrastructure—posits that for every $1 spent on such infrastructure across 4,000 projects in 2019 and 2020, $87 was spent on infrastructure projects without climate resilience strategies.5 This fact compliments findings from McKinsey that the world needs to spend up to $3.3 trillion per year through 2030, on infrastructure, to sustain economic growth in the face of climate change.6

In other words, the playground is shrinking.

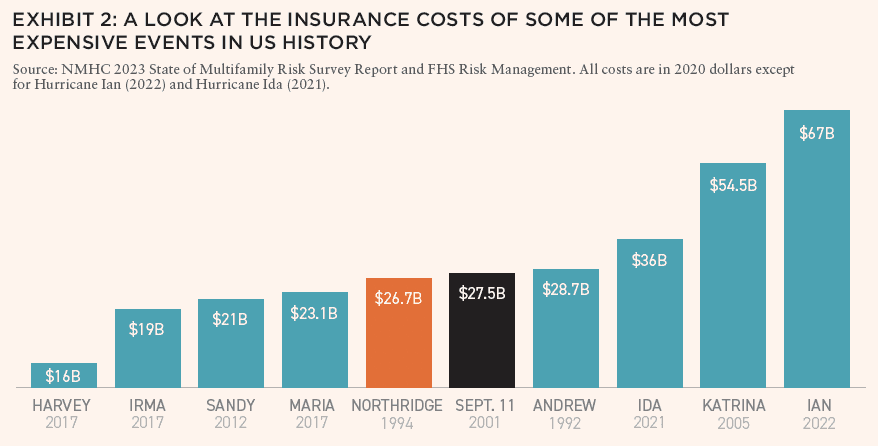

Increasingly, especially in regions with low climate resilience (i.e., a lack of appropriate infrastructure), insurers are demanding similar enhancements or upgrades—all of which come at a cost, which have likewise been exacerbated by supply and labor challenges over the past several years. And the pressure is mounting as climate change worsens, with eighteen of the twenty-two most expensive insurance events in US history occurring in the past twenty years alone (Exhibit 2).7

None of these facts and figures surprise the commercial real estate industry, and at this later stage of climate change, it has become a cliché to point to the insurance business as the canary in the coal mine. The bird is well in flight and covered in soot. But outside the mine, and looking at a different side of the landscape, there is a coming tide of loans coming to term, and many institutional-grade assets, such as once-prized trophy office assets, facing the pressure to adapt (i.e., in the face of changing cultural attitudes around office usage) or die. And of course, investment in climate resilience is a necessary point of adaptation—and in some cases, it’s the ultimate adaptation.

In conversations across commercial real estate, including here in Summit Journal, there is fomenting about repricing, revaluations, and distress—all of which present a unique opportunity to the next generation of real estate investment to use potential savings as a means to invest in both building and infrastructure resilience. Sacrifice won’t be optional, but at this point, neither is climate change.

IN THIS ISSUE

NOTE FROM THE EDITOR: WELCOME TO #14

Benjamin van Loon | AFIRE

INSURING FOR ELSEWHERE: CLIMATE-RESPONSIVE REAL ESTATE INVESTMENT

Benjamin van Loon | AFIRE

INSURING FOR ELSEWHERE: STRIPPING THE CASHFLOW FROM THE DEAL

Paul Fiorilla | Yardi

MARKET OUTLOOK: MODEST GROWTH AND RETREATING INFLATION IN 2024

Martha Peyton, CRE, PhD | LGIM America

UNDERPERFORMANCE PARADOX: NEW RESEARCH QUESTIONS THE VALUE OF PRIVATE REAL ESTATE FUNDS

William Maher, Taylor Mammen, Ben Maslan | RCLCO Fund Advisors

NAVIGATING THE CURVE: RESILIENCE, ADAPTATION, AND PREPARING FOR 2024

Jack Robinson, PhD | Bridge Investment Group

LIQUIDITY FREEZE: POTENTIAL SOLUTIONS FOR COMMERCIAL REAL ESTATE

Christopher Muoio | Madison International Realty

SUPPLY WAVE: REASON FOR OPTIMISM IN THE MULTIFAMILY SECTOR

Sabrina Unger, Britteni Lupe | American Realty Advisors

MANAGE WHAT YOU MEASURE: UNDERSTANDING EXPENSE INFLATION IN APARTMENTS

Gleb Nechayev | Berkshire Residential + Webster Hughes, PhD | ThirtyCapital

PARSING OFFICE DISTRESS: PLANNING FOR THE NEXT GENERATION OF OFFICE SPACE

Dags Chen, Lincoln Janes, CFA | Barings Real Estat

MODEL STATES: USING ECONOMIC STATE MODELS TO ASSESS THE US OFFICE OUTLOOK

Armel Traore Dit Nignan | Principal Real Estate

OUTWARD SHIFT: WILL THE LOGISTICS SECTOR CONTINUE TO OUTPERFORM?

Kerrie Shaw | AXA IM Alts

HARNESSING THE WIND: TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGE AND THE PROMISE AND PERIL OF AI FOR REAL ESTATE

Nikodem Szumilo | University College London + Chris Urwin | Real Global Advantage

MIND YOUR DATA: REAL ESTATE INVESTING, FROM THE POINT OF VIEW OF A DATA NERD

Ron Bekkerman, PhD

OPERATING EXPENSES RISING THE OTHER MAJOR COMPONENT OF NOI GETS MORE FOCUS

Stewart Rubin, Dakota Firenze | New York Life Real Estate Investors

IN MEMORIAM: JANICE STANTON

+ LATEST ISSUE

+ ALL ARTICLES

+ PAST ISSUES

+ LEADERSHIP

+ POLICIES

+ GUIDELINES

+ MEDIA KIT (PDF)

+ CONTACT

—

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Benjamin van Loon is the Editor-in-Chief of Summit Journal. In 2023 he was named as one of the “Forty Under 40” Association Leaders by Association Forum.

—

NOTES

1. SRM Institute of Science and Technology. “Climate Responsive Architecture.” Accessed February 1, 2024. https://webstor.srmist.edu.in/web_assets/srm_mainsite/files/downloads/climateresponsivearch.pdf.

2. “Most Climate-Resilient Cities.” Architectural Digest. Accessed February 1, 2024. https://www.architecturaldigest.com/reviews/solar/most-climate-resilient-cities.

3. “South Florida Resort.” Developing Resilience – Urban Land Institute. Accessed February 1, 2024. https://developingresilience.uli.org/case/south-florida-resort/.

4. “Resilient Infrastructure.” Milken Institute. Accessed February 1, 2024. https://milkeninstitute.org/programs/resilient-infrastructure/.

5. “Tracking Investments in Climate-Resilient Infrastructure.” Climate Policy Initiative. Accessed February 1, 2024. https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/publication/tracking-investments-in-climate-resilient-infrastructure/.

6. “Voices on Infrastructure: Insights on Project Development and Finance.” McKinsey & Company. Accessed February 1, 2024. https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/business%20functions/operations/our%20insights/voices%20on%20infrastructure%20insights%20on%20project%20development%20and%20finance/voi%20insights%20on%20project%20development%20and%20finance.pdf.

7. “Multifamily Risk Management: An Industry Overview.” National Multifamily Housing Council. Accessed February 1, 2024. https://www.nmhc.org/globalassets/research–insight/research-reports/insurance/nmhc_mf_risk_flyer.pdf.

—