This article appears in Summit Journal (Summer 2020) | Download PDF

Want more? Listen to AFIRE Podcast #10: A Real Estate Reckoning.

AROUND THE WORLD, 2020 HAS BEEN RIFE WITH PUBLIC HEALTH ANXIETIES, CIVIL UNREST, ECONOMIC UNCERTAINTIES—NOTHING NEW FOR REAL ESTATE, BUT WHAT DOES IT MEAN FOR THE FUTURE?

In his famous poem “The Second Coming,”¹ composed as the world faced the Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918, William Butler Yeats wrote:

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Those words once again apply in the summer of COVID-19. Governments, economies, and regular people struggle to hold things together as the assumptions and structures they relied on six months ago fall apart.

Amid the pandemic, systemic inequity and injustice can no longer be ignored or put aside, especially the less fortunate endure the worst impacts of this crisis. The Black Lives Matter protests in the US, provoked in part by yet another incident of police brutality, is a wake-up call characterized by strong language, painful stories, and uncomfortable truths.

Everyone now is paying attention. Difficult and sensitive conversations across the membership of AFIRE return again and again to the need for better understanding of this complicated issue. There is no easy way to talk about it—true emotional maturity, patience, and humility are required. The problems addressed by the protestors call for much more than another corporate diversity initiative. They ask for meaningful change while empathetic and supportive people everywhere ask, “what can we do?” It is a very difficult question to answer.

When problems are this big, the first instinct is to avoid them, which is completely understandable but not wise. Fortunately, leaders in real estate are accustomed to large, complicated, and uncertain problems that take many years of trial, error, and humility to solve. No one has all the answers, no one is without flaws in their thinking, and no one succeeds without listening and learning. Real estate has asked this question many times before: is it possible to support a more sustainable and profitable future for everyone?

Yes, it is.

But first, some uncomfortable truths must be faced: Racism is a very real and pernicious aspect of the US and other countries around the world. There are both conscious and unconscious obstacles to equity and inclusion built into environments, practices, and policies. Everyone, no matter their politics, level of success, skin color, or social status, struggles with some level of unconscious bias and fears. This is a deep-rooted problem that will take a significant amount of time, listening, reflection, and methodical work by individuals and institutions to solve. On this point, it is inspiring to reflect on the words of playwright Bertolt Brecht: “Weil die Dinge sind, wie sie sind, werden die Dinge nicht so bleiben wie sie sind” (Because things are the way they are, things will not stay the way they are).

All levels of government and society need to learn and acknowledge that current practices stand in the way of true equity. Real estate has to do so as well. Intentionally or not, our industry has played a part in systemic racism. Most egregiously, and rightfully criticized by many, there are outlier examples in the present day of commercial property owners intentionally excluding minority tenants. And even though institutional real estate is usually more careful and informed, no organization is without bias. Racism is there, but it may be less obvious. The diversity of employees and leaders within real estate firms has been an issue discussed by many organizations for some time, but there is a long way to go before the industry truly reflects the diversity of the overall population. Meanwhile, real estate lending and development has quietly supported the same tenets of inequity that lead to precisely the exclusivity and lack of diversity they otherwise denounce. Lending practices described by sociologist John McKnight in the 1960’s as redlining—official or not— continue to deny minorities the same access to mortgages for homes even today. Inequitable development practices ranging from the construction of transit corridors to gentrified displacement of urban minority populations, can reinforce racial barriers even when they are not intended to do so. Racial deed restrictions and covenants were common practices well into the second half of the twentieth century.

Today, the US is becoming more diverse, but slowly, and too many neighborhoods are still segregated. According to Maria Krysan and Kyle Crowder in their book, Cycle of Segregation, “segregation by race has become self-perpetuating, driving systems of economic stratification, shaping neighborhood perceptions, circumscribing social networks and systems of neighborhood knowledge by race and ethnicity, and creating patterns of mobility and immobility that differ sharply across racial and ethnic groups.”² The divisiveness of US politics is a very tangible symptom of a society where location, socio-economic status, beliefs, and racial categories are inextricably linked. In the early 1900’s, the term melting pot was popularized to describe the powerful fusion of cultures, ethnicities, and origins of the US population. Where people live and work today is keeping the US melting pot from working the way it should.

These and other practices are part of a status quo that real estate leaders need to understand, acknowledge, and ultimately change.

RACIAL GEOGRAPHY IN THE US

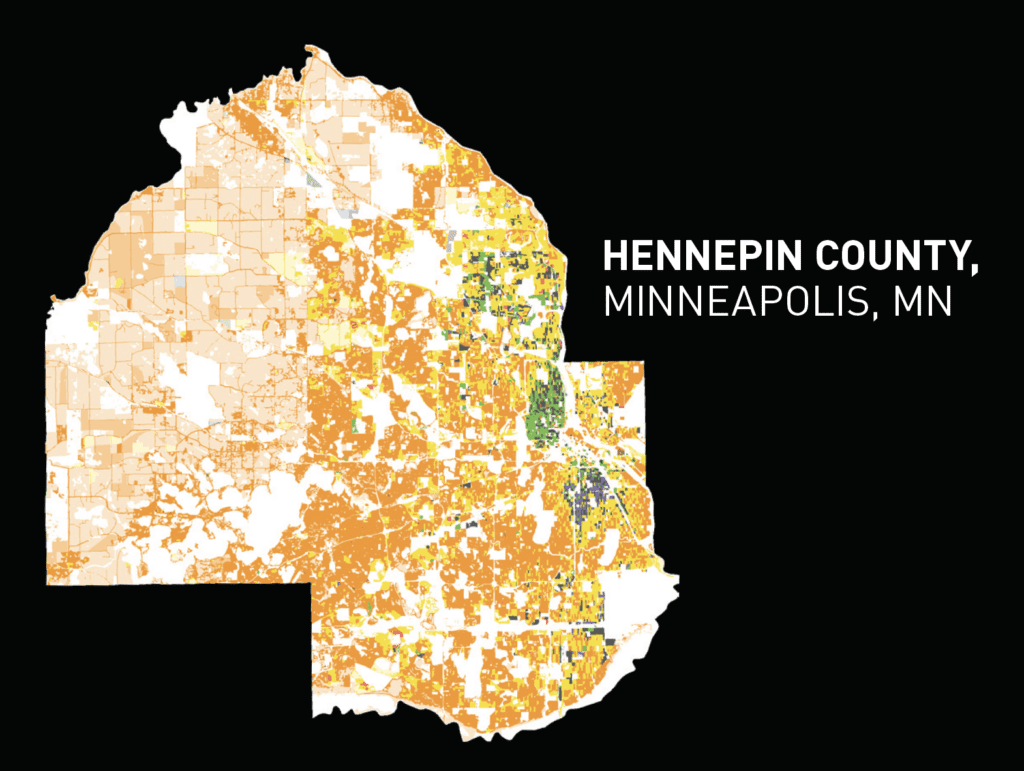

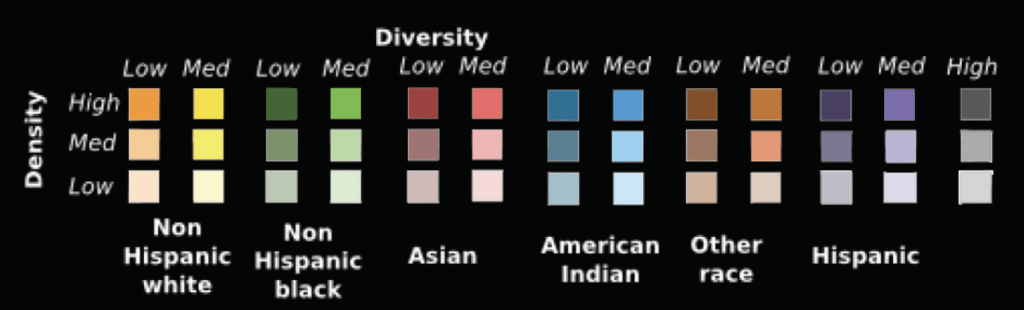

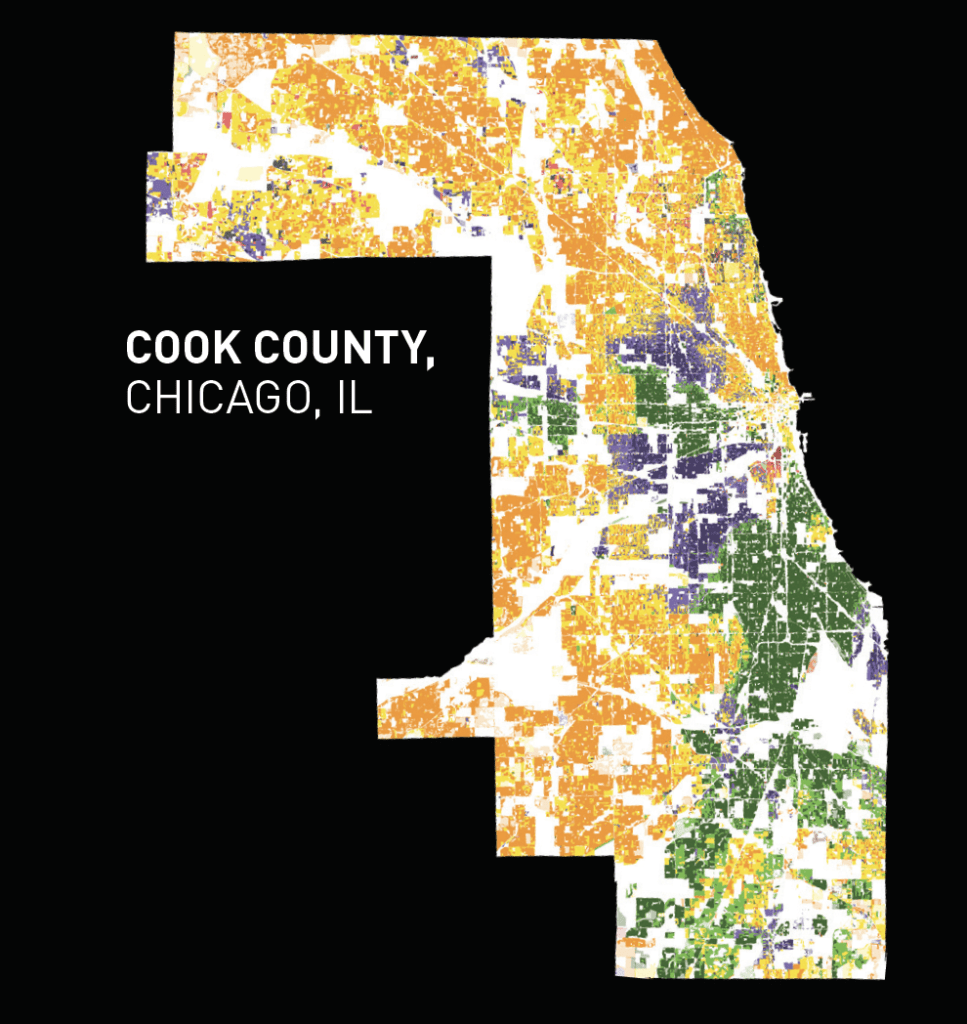

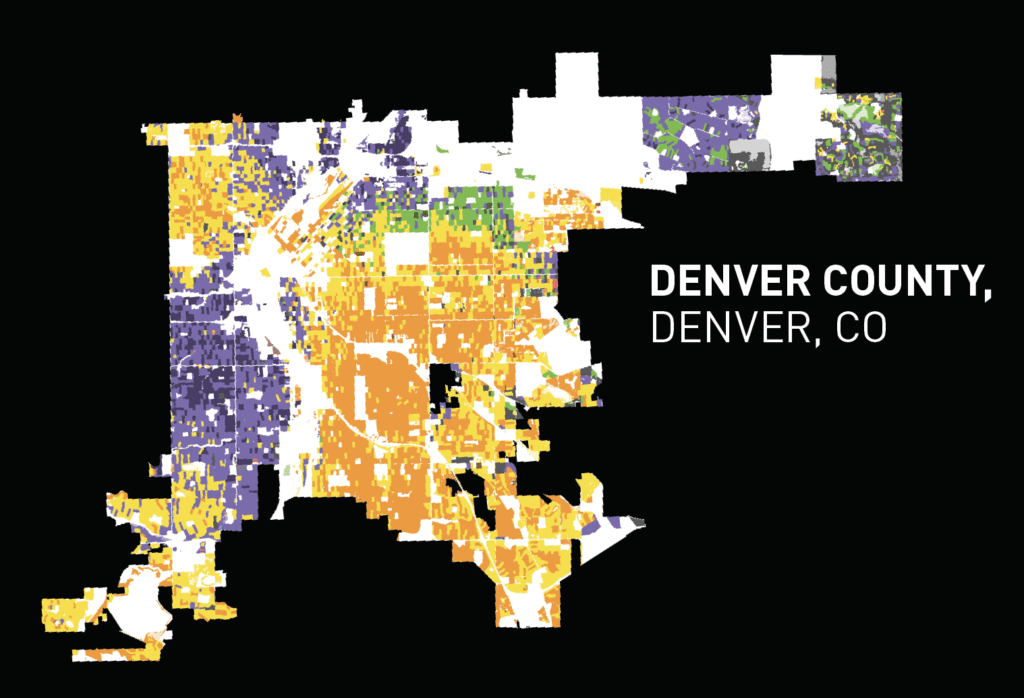

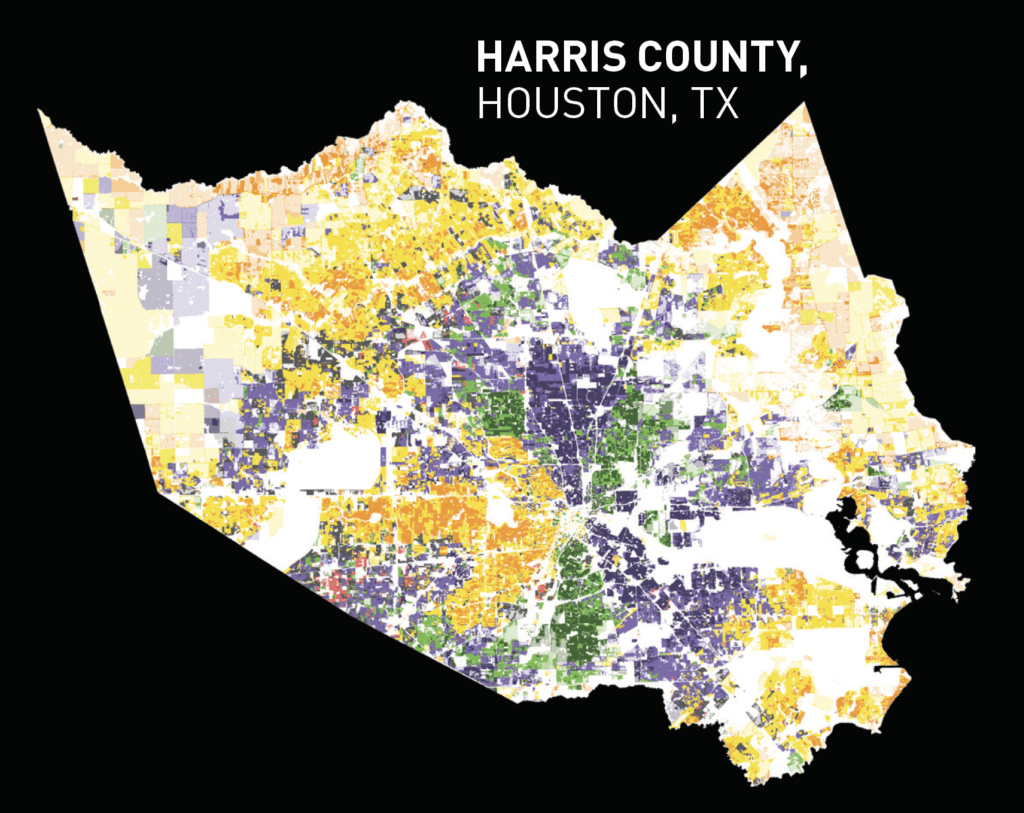

Visualizing demographic data from the most recent US census (2010) creates a stark image of “unofficial” segregation and the result of inherited, racially-motivated, legacy policy decisions in some of the most populous US counties. (Maps and data courtesy of the University of Cincinnati Space Informatics Lab.)

Official census classification of race/ethnicity has evolved over the past century. Because the data on this page is extracted for a decade-by-decade comparison of demographic changes, the maps draw on the five primary race/ethnicity categories recognized in the US census through 2010: Non-Hispanic Whites, Non-Hispanic Blacks, Non-Hispanic Asians (including also American Indians), Non-Hispanic Others, and Hispanic/Latino origin population.

Visualized data, entirely licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, includes patterns in high-resolution demographic grids covering the entire conterminous US. At present the site includes two demographic variables: population density and racial diversity. Currently, grids for 1990, 2000 and 2010 year are available.

Source: A. Dmowska and T.F. Stepinski, “High Resolution Dasymetric Model of US Demographics with Application to Spatial Distribution of Racial Diversity,” Applied Geography 53: 417-26

Most institutional investors do not wish to exclude or divide anyone, especially as they invest pension money and the savings of ordinary people from around the world—and have an implicit duty to invest for that diverse constituency. They have a particular fiduciary imperative to invest for the long term and therefore to understand, acknowledge, and act in a way that supports a more stable and just environment for the long-term success of investments as well as the users of real estate.

After a historically long economic recovery following the Great Financial Crisis, investors have complained of a limited amount of attractive investment opportunities. Of course, most prefer to focus on real estate that has financially secure and established tenancy in the best neighborhoods, and usually define those properties as “core” investments. Due to economic disparity, most of the non-White users of real estate end up in “noncore” buildings. Implicit in a core investment strategy is the idea that underdeveloped neighborhoods are not as attractive. Some investors, however, have already discovered that this is not necessarily true.

The former basketball star-turned-real estate investor Earvin “Magic” Johnson found outstanding returns in areas that have been historically overlooked. According to Johnson, “When you think about African Americans now—over $1 trillion spending power— Latinos, over $1 trillion spending power, and moving even higher—there was nobody really building businesses and going after their disposable income.”³

Seeing this same “hidden” value, there are a few that focus on investing in overlooked communities, including real estate developers and investor groups such as Direct Invest Development, Avanath Capital Management, Abode Communities, and others. Their approach attracts institutional capital due to favorable risk adjusted returns. It can be done, it should be done, and it is in the best interests of institutional capital’s constituents to get it done.

As big and as uncomfortable as the issue of racial equity is, institutional investors are particularly well equipped to examine practices and lead change. Over the last 20 years, this industry began to face one of the most complicated and existential threats to the social, economic, and environmental order: global climate change. Real estate became a significant leader with new sustainability practices, ESG investing metrics, and strategies. Unimaginable changes in the way the world constructs and manages buildings have become standard, because institutional capital decided it had to be done. Of course, achieving true sustainability is something that will take a significant number of years to accomplish, and real estate is still early in the process— but as a group, institutional investors examined the problem, acknowledged their part in it, and began to work towards a sustainable future, even as other industries struggled to keep up.

The same thing can be done with equity, inclusion, and diversity. This is hard, this is uncomfortable, this is big and complex, but it is an essential issue to address. There is an opportunity for the industry to lead, if we listen, honestly face the problems, and act with humility. On this point, American writer and civil rights thought leader James Baldwin said it best: “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

—

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Gunnar Branson is the CEO of AFIRE, the association for international real estate investors focused on commercial property in the United States.

—

NOTES

1. William Butler Yeats, The Collected Poems of W. B. Yeats, Edited by Richard J. Finneran. New York: Macmillan, 1983.

2. Maria Krysan and Kyle Crowder, Cycle of Segregation: Social Processes and Residential Stratification, New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2017.

3. Kathleen Elkins, “How Magic Johnson Convinced Howard Schultz to Partner with Him and Build more Starbucks Stores,” CNBC.com (November 10, 2018): cnbc.com/2018/11/09/how-magic-johnson-gotstarbucks- ceo-howard-schultz-to-partner-with-him.html

—