US garden apartment investments are offering outsized return potential—but access remains a challenge.

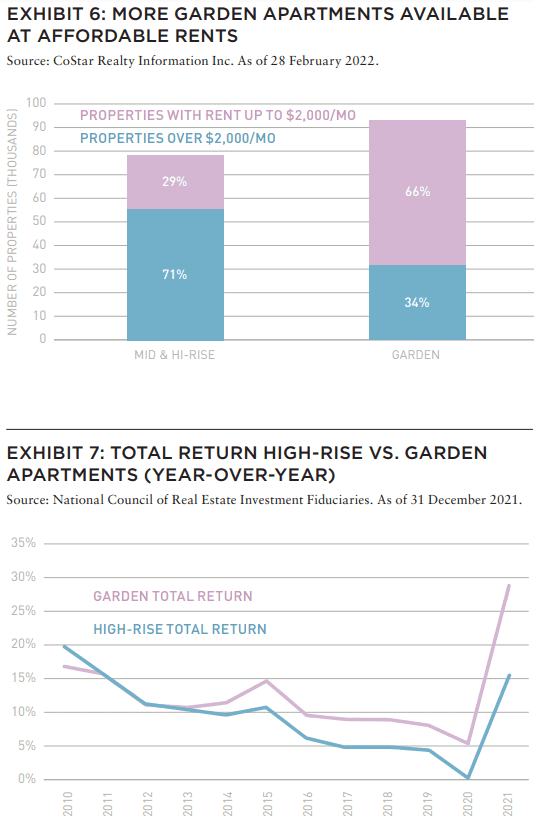

The garden apartment subtype of the apartment sector is producing very encouraging total returns for property investors, beating all sector returns outside of industrial. The outperformance of garden apartments prevailed throughout 2021, but over the twenty-year average as well.1

However, such properties have also not traditionally been held by institutional investors, which have historically focused more of their apartment holdings on high-rise properties where new construction is more plentiful.

A LOOK BACK

In 2021, institutional investors appeared to be noticing the attractiveness of garden apartment properties as net acquisitions more than doubled versus the ten-year average. Joint ventures comprised more than a fifth of this activity.2

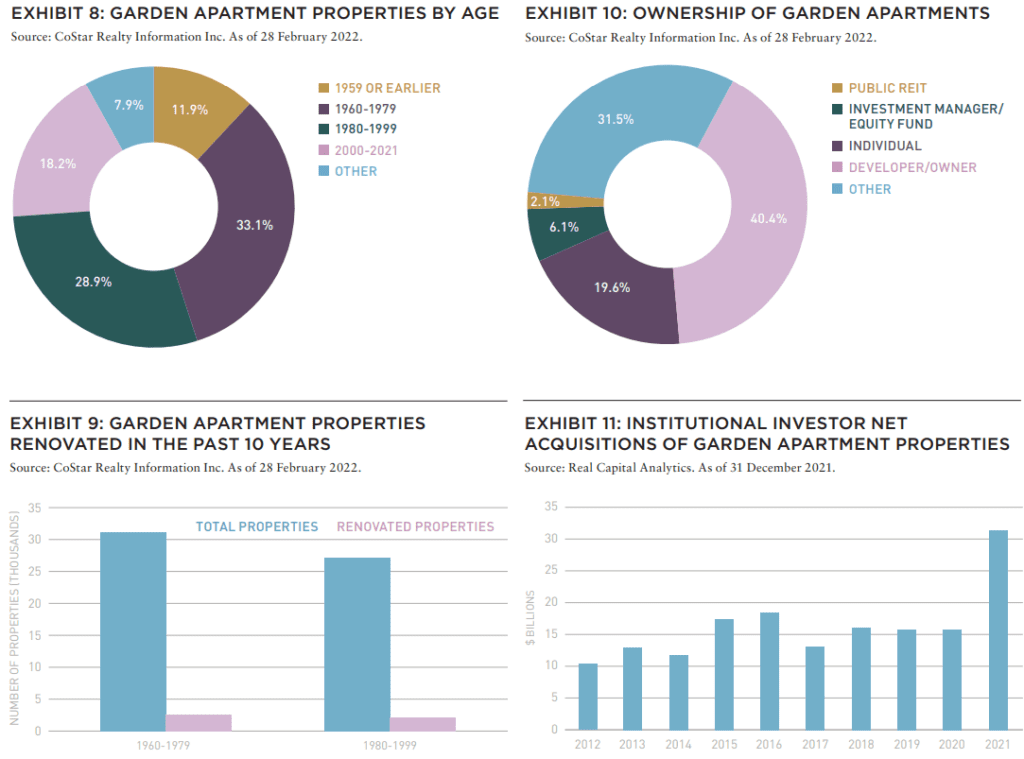

In light of the generally older vintage of garden apartment stock, more investment opportunity is available—especially for value-add investments that will prolong the useful life of these properties.

In light of the generally older vintage of garden apartment stock, more investment opportunity is available—especially for value-add investments that will prolong the useful life of these properties.

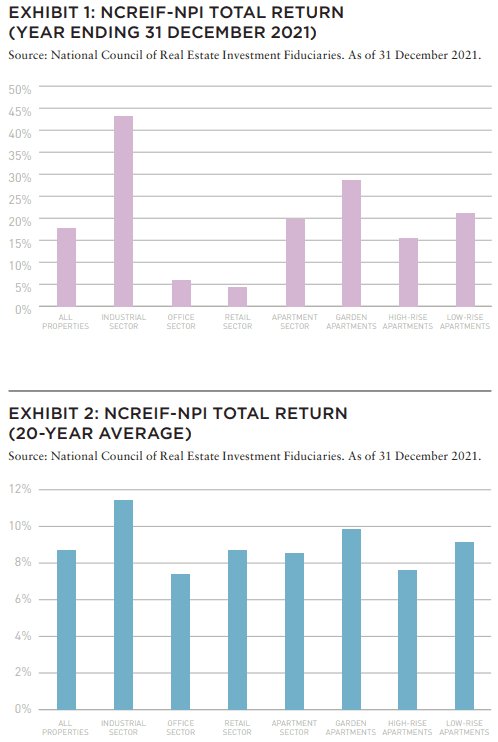

Investors in US commercial property have been solidly rewarded for understanding the apartment sector and its subtype nuances. In 2021, apartments were the second strongest performing sector, with total return of 19.9%. This performance handily beat the all-property total return of just over 17%. Within the apartment sector, garden apartment properties posted a stunning total return of almost 29% (Exhibit 1). This performance rewarded investors for focusing their capital away from architecturally striking high-rises (defined as four stories or taller) and toward more conventional garden apartments (defined as three stories or less on “sizable” landscaped lots).1

The impressive performance of garden apartments is not surprising given an intense backdrop comprised of a pervasive national housing affordability burden and barriers to homeownership. However, it bears noting that superior investment returns for garden apartments versus both high-rise and low-rise properties (defined as three stories or less, typically in one structure) has prevailed for the last twenty years. Moreover, as shown in Exhibit 2, as of 31 December 2021, the twenty-year average of garden apartment total returns bested the performance of the total of all properties, as well as that of the office and retail sectors separately. Only the industrial sector produced a better twenty-year average total return performance.

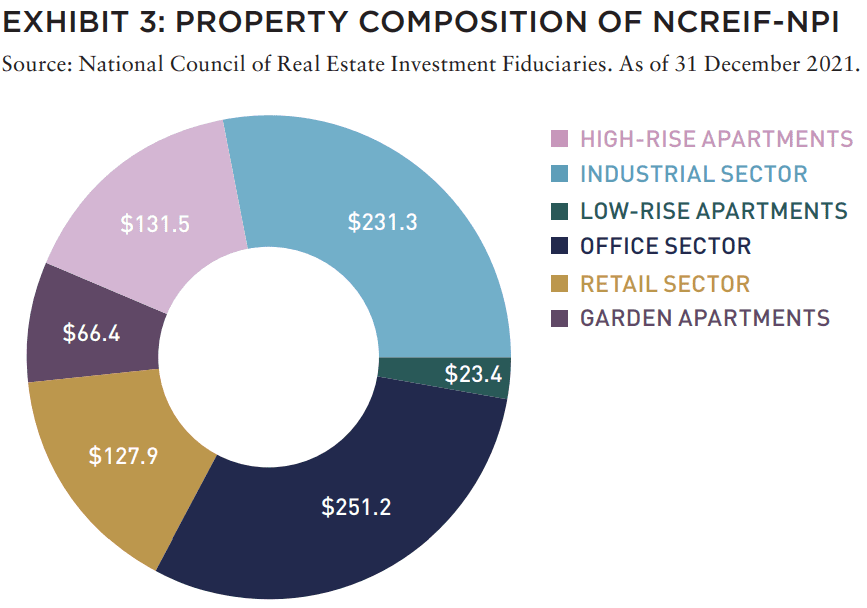

Property portfolio managers are doubtlessly well-aware of the superior performance of garden apartments versus both high-rise and low-rise apartment sub-types. Yet, holdings in the NCREIF National Property Index (NCREI-NPI) portfolio, tilt toward high-rise properties which totaled US$132 billion and 1,085 properties as of 31 December 2021, versus US$66.4 billion and 753 properties in the garden sub-type (Exhibit 3). The tilt is surprising not only because of the historical difference in total return performance, but also due to the historical difference in cap rates: The twenty-year average cap rate for garden apartment properties in the NCREIF-NPI is 5.5% versus 4.8% for low-rise properties and 4.6% for high-rise.1

ATTRACTION OF HIGH-RISE PROPERTIES DIMMING

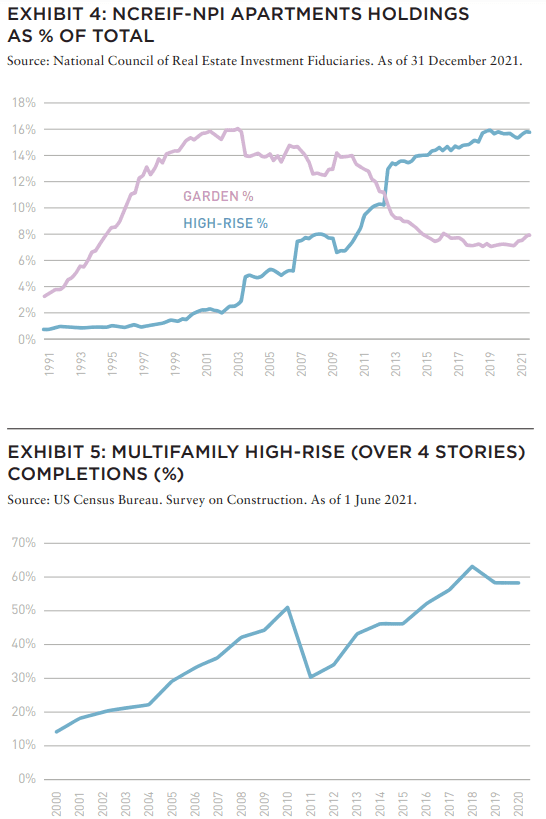

High-rise apartments overtook garden apartments as a percent of the NPI portfolio in 2012 after a prolonged period of slow convergence (Exhibit 4). The pace of high-rise allocation accelerated after 2000 and corresponded to an accelerating pace of high-rise construction that plateaued in 2018 (Exhibit 5).3 In that year, more than 60% of apartments under construction were in buildings of at least fifty units.4 The surge in high-rise construction responded to renewed interest in cities, especially as millennials (b. 1981–1996) matured. Investors recognized their preference and were attracted to high-rises partly because they make maximum use of expensive land to create the highest quality apartments at the highest rents that a given location can bear. High-rises also offer deal sizes that are relatively large. High-rises in the NPI average US$121.2 million versus US$88.2 million for garden apartment properties. The lag in high-rise investment performance reflects too much of a good thing when developers overshoot market demand that has perhaps been influenced by maturing millennials looking for more spacious garden apartments in the suburbs.

Garden apartments are less subject to demand-supply imbalances because they are less dense, with generally lower rents, and therefore less attractive for developers. As shown in Exhibit 6, 66% of garden apartments have rents of US$2,000/month or less versus only 29% of denser apartment properties. The lower rent profile of garden apartments is crucial in light of affordability constraints. Solid demand and relatively inelastic supply have helped total return on garden apartments to beat high-rises every year since 2014 (Exhibit 7).

The affordability issue is well-illustrated in metrics showing that roughly 24% of renter households were severely cost-burdened in 2019, paying 50% or more of household income for housing, while another 22% of renter households were moderately costburdened, paying 30%–50%. Middle-income households in the US$30,000–US$74,999 income cohort were not spared, with 41% reported as cost burdened.5

Overall rental housing affordability is not likely to improve in the years ahead. On the demand side, student debt will continue to weigh on younger renter households without enough income growth to materially ease the burden. J.P. Morgan reports that 40% of millennials have student debt and that it consumes 40% of their income on average.6 Moreover, single-family home prices and mortgage down-payment requirements put homeownership out of reach for many. A recent survey of millennials finds that only 15% have set aside $10,000 or more for a home purchase down-payment.7 On the supply side, as long as land prices remain high, apartment developers will continue to have incentive to build high-rises. These conditions will likely continue to promote attractive investment prospects for the more affordable garden apartment segment of the rental universe.

SIZING THE INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY

Costar data show a total of almost 94,000 garden apartment properties scattered across the US.8 The bulk of these properties were built between 1960 and 1999 (Exhibit 8). Few of these properties were renovated during the last ten years, suggesting that most need attention—if not extensive renewal (Exhibit 9). The capital expenditure needs of these properties provide investors with an opportunity for making careful value-add improvements that can produce higher rents and longer useful life. As long as rents remain affordable compared to alternatives, investors can garner incremental return.

Despite this opportunity, Costar data shows that ownership of garden apartment properties is concentrated among developer-owners holding 40% and individuals holding 20% (Exhibit 10). Properties owned by developers are largely medium- to lower-quality; only 18% of their 47,810 properties are in the highest quality category. For individual owners, almost 100% of holdings are in medium to lower quality categories. Investment managers and equity funds hold only 6% of garden apartment properties.8

In recent months, institutional investors seem to be paying more attention to the attractiveness of garden apartment properties. Their 2021 net acquisitions were more than 110% over the average of the prior nine years (Exhibit 11). Moreover, more than a fifth of those acquisitions were joint ventures typically involving developer-owners. Such ventures might be undertaking value-add capital expenditures, or perhaps they simply reflect an appetite for experienced property management.

Institutional investors may be recognizing the attractiveness of garden apartment investments in light of their strong investment performance, depth of stock and value-add opportunities. Ongoing, pervasive affordability limits and homeownership constraints support demand for garden apartment rentals, while supply remains constrained by developers’ preferences for high-rises.

—

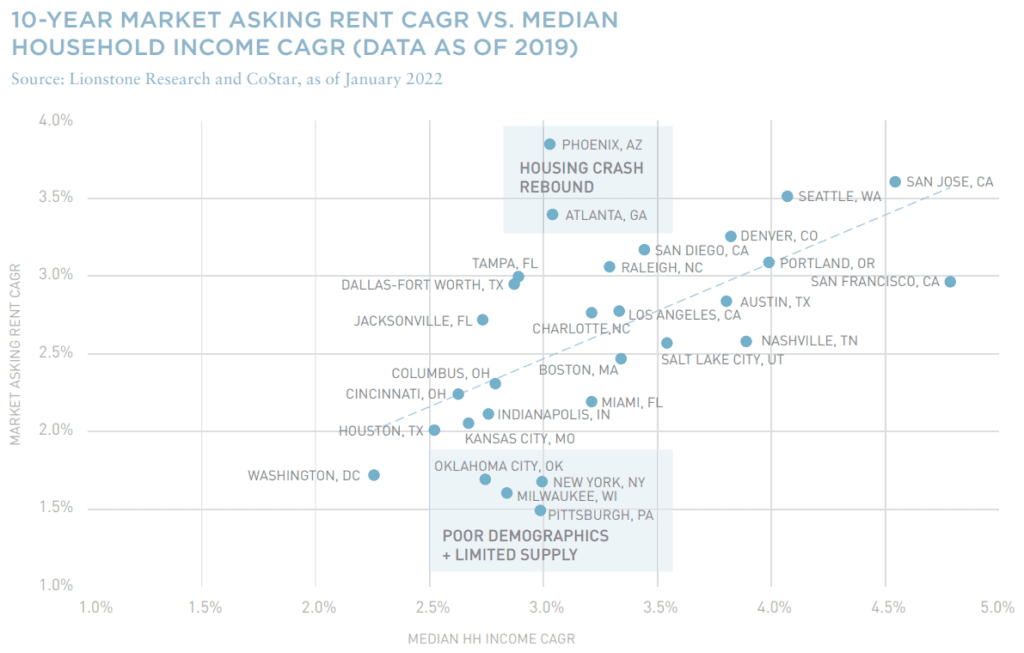

The data in the article speaks and is compelling. On a national average basis, high-rise and high rent properties have underperformed compared to low-rise and low rent properties. Moreover, prospects for future garden apartment demand growth appear bright due to housing unaffordability. That said, with US population growth plummeting and migration moving away from the demand centers of the pre-pandemic decade, this excellent analysis might be cut a little finer for future investments.

Until recently, some analysts believed garden apartment investment broadly benefitted from sale prices below replacement costs. In effect, these assets were sheltered from the impact of new supply as it was not economical to build non-high-rise suburban or non-CBD-urban apartments. Today, sales prices for garden style assets often appear to be above replacement cost, stimulating supply in low-rise assets where development was not previously economical. As a result, the dynamics of investing in garden-style apartments might require even more careful analysis of where local income growth can support already onerous rent burdens.

As the author points out, more institutional investors are moving into the garden apartment space and prices are rising. As a result, it may behoove investors to also focus on geographies enjoying household income growth, which is highly correlated with rent growth. The downside exceptions occurred when overall population growth was low and development versus demand growth was high, a risk that bears watching in the 2020s.

Hans Nordby

Editorial Board Member, Summit Journal

Head of Research and Analytics, Lionstone Investments

—

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Martha Peyton is Managing Director of Applied Research for Aegon Asset Management, the global investment management brand of Aegon Group.

—

NOTES

1National Council of Real Estate Investment Fiduciaries, ncreif.org, accessed December 31, 2021.

2Real Capital Analytics, rcanalytics.com, accessed December 31, 2021.

3“New Residential Construction,” United States Census Bureau, census.gov/construction/nrc/index.html, accessed June 1, 2021.

4“America’s Rental Housing 2020,” Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, jchs.harvard.edu/americas-rental-housing-2020, accessed April 29, 2022.

5“America’s Rental Housing 2020,” Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, jchs.harvard.edu/americas-rental-housing-2020, accessed April 29, 2022.

6Jack Manley, “Millennials: Unique Challenges for Younger Investors,” JP Morgan Asset Management, updated July 14, 2021, am.jpmorgan.com/us/en/asset-management/adv/ insights/market-insights, accessed April 29, 2022.

7Rob Warnock, “Apartment List’s 2021 Millenial Homeownership Report,” Apartment List, updated February 9, 2021, apartmentlist.com/research, accessed April 29, 2022

8 CoStar, costar.com, accessed December 17, 2021. Data excludes military, dorms, condos, co-ops, and vacation units.

EXPLORE THE FULL ISSUE (SPRING 2022)

MARCHING BACKWARDS INTO THE FUTURE

The new 2022 AFIRE International Investor Survey Report reveals future institutional investment trends as the pandemic transformed how we live, work, and play.

Gunnar Branson and Benjamin van Loon | AFIRE

CITIES THAT WORK

What is it that makes London, Stockholm, Berlin, Amsterdam, and Paris the top European cities for office investment? And what could this mean for other global cities?

Dr. Megan Walters | Allianz Real Estate

SURVEY SURFEIT

Be careful about advice you hear from surveys— it will not always play out as expected.

Jim Costello | MSCI Real Estate

NEW WORKING AGE

Outside of WWI and II, the US working age population has never declined. As of 2021, that statement is no longer true.

Stewart Rubin and Dakota Firenze | New York Life Real Estate Investors

SELECTIVE FRAMEWORK

Two years after offices closed due to the COVID pandemic, the debate over the longterm future of the office continues. What should office investment look like going forward?

Dags Chen, CFA; Ryan Ma, CFA; and Ryan LaRue | Barings Real Estate

GARDEN VIEW

US garden apartment investments are offering outsized return potential –but access remains a challenge.

Martha Peyton, PhD | Aegon Asset Management

SINGLE-FAMILY DEMAND

As an increasingly popular asset class for institutional investors, single-family rentals are supported by strong future demand drivers to propel sector outperformance.

Daniel Manware | Nuveen Real Estate

ESSENTIAL HOUSING

The US is in the middle of one of the biggest housing crises that the country has ever seen. It needs a more resilient approach to housing.

Todd Williams | Grubb Properties

LODGING TAKES THE LEAD

As a labor-intensive and service oriented asset class, hospitality is uniquely positioned to be a leader in advancing sustainability goals for investors.

Charlotte Kang, Geraldine Guichardo, Lori Mabardi, and Emily Chadwick | JLL

CARRY ON, CARRY OVER

While continuation vehicles were once viewed as a signal of delay or failure, market sentiment is rapidly changing.

Max LaVictoire and Ashley Anderson | Hodes Weill & Associates

RENEWING ETHICS

A note from AFIRE’s Ethics Chair on the need for maximizing ethics in an age where globalization is under threat.

El Rosenheim | Profimex