The investment community can have an active role in an equitable economic recovery—but it will require the necessary discomfort of recasting the traditional risk/return framework.

Recessions typically put a hard stop to development. Shrinking economic activity, loss of jobs, and uncertainty about the recovery make it more challenging for developers and lenders to greenlight projects. But this pandemic-induced recession is different, because the supply/demand balance heading into it was not too out-of-sync with economic realities, and the amount of leverage in the ecosystem was not too onerous. More importantly, the pandemic and the uneven K-shaped recovery have magnified and laid bare some deeply ingrained systemic deficits in housing, healthcare, education, retail, and other services for minority and other disadvantaged communities.

The pandemic has also accelerated many of the demographic trends already underway shaping demand for housing such as millennials facing affordability and scarcity issues as they enter the home-buying stage of their lives. The current housing infrastructure is not prepared for the massive shifts in demand.

It is apparent, then, that the development cycle needs to rev up in earnest to respond to these challenges. Not doing so would be inexcusable in light of the reckoning from a year of equity-focused protests and the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on certain neighborhoods and communities.

The investment community can support this rev-up endeavor— it is possible to be good and profitable—though it may require recasting the traditional framework of risk and return. Is “risk-free” or “low-risk” development that reinforces systemic inequality and injustice truly risk-free and equitable? What are the hidden costs of ignoring the obvious disparities in access to housing and other services?

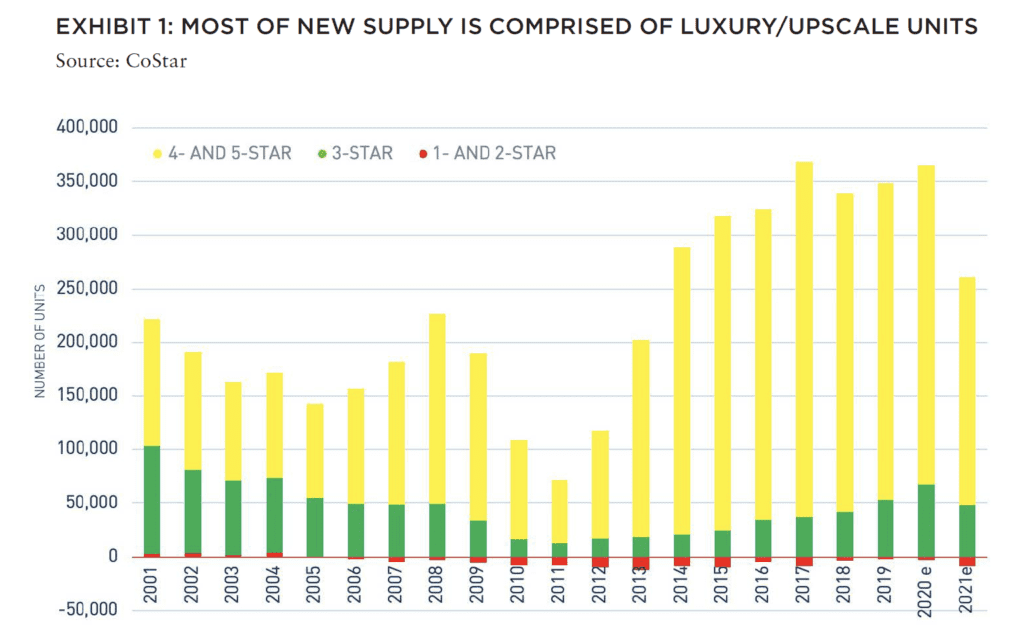

Leading up to the pandemic, the decade-long housing development cycle in the post-GFC era had focused almost single-mindedly on luxury rental housing (Exhibit 1) in a narrow subset of submarkets in most metros.

The more “affordable/workforce” segment of the for-rent sector, and a majority of neighborhoods have not seen a significant inflow of investment dollars, despite growing concerns about housing-related cost-burdens facing many households. Add to that the issues of gentrification and displacement many inner-city neighborhoods experienced where some of the new luxury housing was being built, and the challenge got bigger. It is clear that how housing and infrastructure supporting underserved communities is built needs a deep rethink. The reevaluation around investment in housing infrastructure can be approached with the idea of closing the opportunity gaps at three different levels:

- Supply of product type: Focusing on a differentiated product that addresses the specific needs of cost-burdened households

at market rate/moderately subsidized rates. - Neighborhood selection: Actively pursuing development in communities where public/private investment has been slow to arrive due to “perceived” risks despite great need.

- Developer/investor inclusion: Allocation to local developers/investors that are connected to these overlooked communities in meaningful ways.

THE MISSING MIDDLE—OPPORTUNITIES IN SUPPLY OF PRODUCT-TYPE

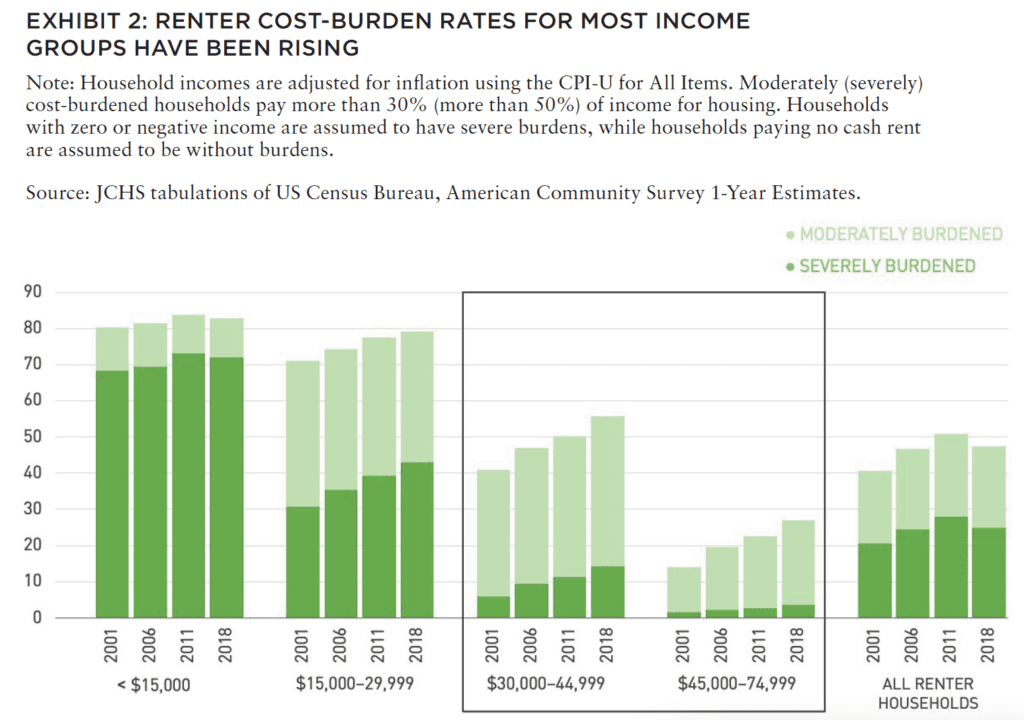

The US was in a rental affordability crisis even before the pandemic. Over the last two decades, renter incomes have fallen in real terms while rents have climbed relentlessly as capital has flowed to building luxury rental housing in affluent neighborhoods. Per the Harvard University Joint Center for Housing Studies (JCHS) latest report, the share of cost-burdened renter households spending more than 30% of their incomes on housing rose from approximately 41% in 2001 to nearly 48% in 2018.[1] Renters earning US$30,000–44,999 annually have seen their share rise 15.4 percentage points, to 55.7%, while households earning US$45,000–74,999 have seen their share increase by 13.3 percentage points, to 27% (Exhibit 2).

The rapidly growing share of cost-burdened middle-income renters is happening in mostly coastal and expensive cities where market-rate rents could be “unaffordable” for even households above 120% area median income (AMI). This has severely impacted the ability of essential employees such as teachers, police, fire, and health personnel, to live in the communities they serve. These essential workers have steady and secure jobs that can pay rent, and they are unable and unlikely to uproot themselves from the communities they work in because of the nature of their jobs. The pandemic has also highlighted the need for other essential staff, such as supermarket and other service workers, to live in closer proximity to their workplaces.

ALSO IN SUMMIT (SPRING 2021)

GREAT LAKES / Tightening the Belts: How are shorthand labels like the “Sun Belt” and the “Rust Belt” shaping investment decisions? Should they?

AFIRE | Gunnar Branson and Benjamin van Loon

SOCIAL ISSUES / The Great Real Estate Reset: A data-driven initiative to remake how and what we build.

Brookings | Christopher Coes, Jennifer S. Vey, and Tracy Hadden Loh

SOCIAL ISSUES / Confronting the Myth: The events of the past year have driven businesses to confront racial inequity, but some still shy away from the challenges needed to make real progress.

Alfred Dewitt Ard Consulting | Shumeca Pickett

INDUSTRY OUTLOOK / CRE Prospects Post-COVID-19: How is commercial real estate set to perform in the post-COVID world?

Aegon Asset Management | Martha Peyton

HOSPITALITY / Time to Check In: If history is a guide, the time to invest in hotels is when things look bleak. This appears to be one of those times.

Barings Real Estate | Jim O’Shaughnessy

HOSPITALITY / Hoteling 2.0: The pandemic has impacted the hospitality, but a growing wave of non-traditional investors has shown heightened interest in the evolving industry.

JLL Hotels & Hospitality Group | Gilda Perez-Alvarado

RESIDENTIAL / Safe as Houses?: The future of residential investments is all about demographics—and the forces behind them.

American Realty Advisors | Sabrina Unger

RESIDENTIAL / Housing for Goldilocks : The pandemic highlights the advantages of single-family and appears to have accelerated migration to less dense, more affordable areas.

GTIS | Eliot Heher and Robert Sun

DATA CENTERS / Data Centers, Stage Center: Data center investments have proven resilient in periods of volatility—and they’re only going to become more essential and important into the future.

Principal Real Estate Investors | Bob Wobschall

CLIMATE CHANGE (WHITE PAPER) / Rather Than the Flood: A comprehensive look at climate-induced water disasters and their potential impact on CRE in the US.

New York Life Real Estate Investors | Stewart Rubin and Dakota Firenze

LOGISTICS / Reforging the Supply Chain: The only way to deliver on the service promises of a booming logistics sector requires a complete reimagination of the supply chain.

Stockbridge | David Egan

DEBT AND LEVERAGE / Leveraging Control: Though leverage is an important part of capital funding, it’s important to ask LPs if (and how) they should take control of their real estate leverage.

RCLCO Fund Advisors | William Maher and Ben Maslan

DEVELOPMENT / Recasting Risk and Return: The investment community can have an active role in economic recovery—but it will require recasting the traditional risk/return framework.

Standard REI | Shubrhra Jha

CORPORATE TRANSPARENCY ACT / Transparency Rules: Non-US-based investors face the disclosure regime of the Corporate Transparency Act. What do you need to know?

Pillsbury | Andrew Weiner

PENSIONS (WHITE PAPER) / Rising Pressures: The latest joint, in-depth report from Praedium and SitusAMC looks at rising fiscal pressures on state and local governments.

Praedium Group and SitusAMC Insights | Russell Appel, Peter Muoio, and Cory Loviglio | SitusAMC Insights

TALENT AND HR / Plugging the Skills Gap: Several trends are forcing change in the global commercial real estate industry, driving demand for new skills. How is the industry responding?

Sheffield Haworth | Max Shepherd

ESG / Operationalizing the Sustainability Agenda: During a time of unprecedented disruption, how should businesses approach the “new metrics” ESG of performance?

AccountAbility | Sunil A. Misser

Another study from JCHS measuring affordability by the residual-income method (after accounting for other essential spending) find that as much as 62% of renter households are cost-burdened.[2] Householders of color, particularly Black and Hispanic renters, are more likely to be burdened. Residual-income burden is 1.2x higher for Black households and 1.1x higher for Hispanic households, when compared to White households. And based on recent data from the Census Bureau’s monthly Household Pulse Survey, the ongoing pandemic has only intensified the crisis in the past year despite eviction moratoriums and other renter support efforts. (See also: “The Great Real Estate Reset.”)

Besides barriers such as restrictive legacy zoning and regulatory issues, building costs in urban areas have increased prohibitively over past several decades. This has incentivized capital to be channeled exclusively to high-end apartments. It has also led to significant investment inflows into the acquisition of moderately priced affordable housing, which are then upgraded with raised rents, further exacerbating the lack of affordable housing. On the other hand, many projects for low-income households (typically below 60% AMI) have access to subsidies or incentive programs, such as low-income housing tax credits (LIHTC) that fill some funding gaps. This disjointed approach leaves a massive hole in the middle.

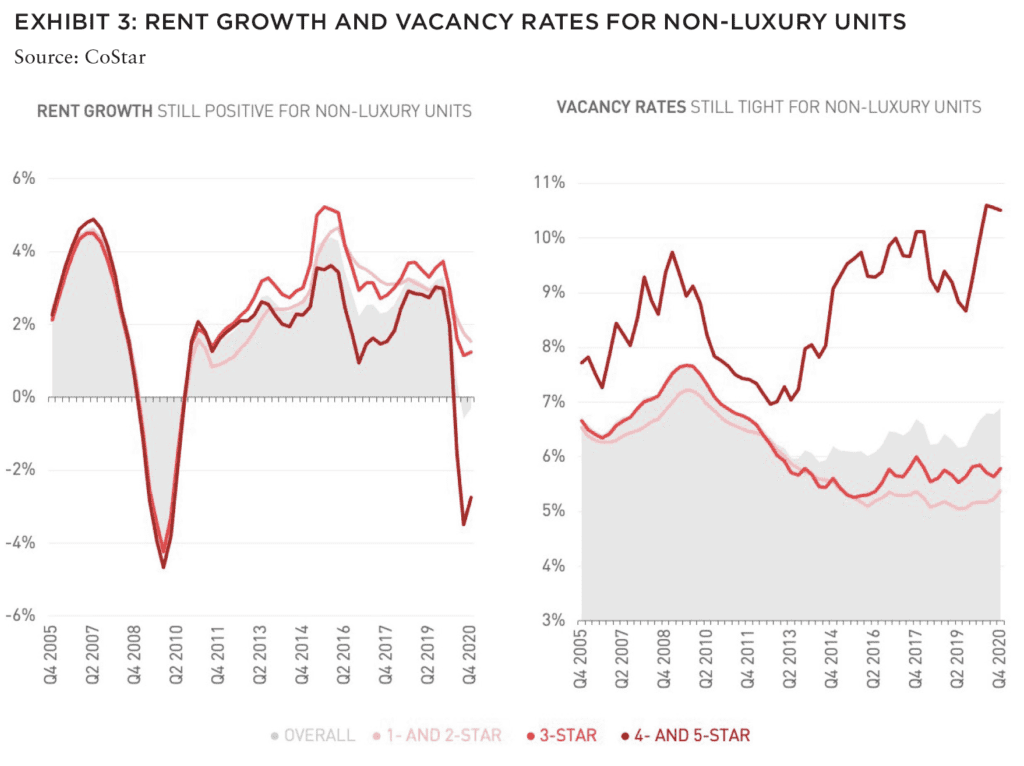

Demand for high-end units have reduced the number of rental units filtering down to lower-or moderate-income households, or even reversed the flow by shifting more units to higher rents through value-add renovations. Building more housing to meet the needs of the middle of the market becomes even more necessary in order to increase supply and reduce affordability pressures on low- and middle-income two-star apartments tracked by CoStar have experienced the least increase during the worst of the pandemic while rent growth has been on the positive side, in sharp contrast to the luxury segment that has seen vacancies spike and rent growth plummet (Exhibit 3).

So how does capital achieve financial returns by building that “missing middle?”

Being creative with financing. Pricing that capital right. Partnering with the public sector. Reversing the arms race of amenities, luxury unit upgrades and finishes. And finally, embracing bold technological and design innovations to bring down construction and ongoing energy costs—while also reducing the carbon footprint. All of these strategies could be in the toolkit for investors.

INVESTMENT DESERTS—OPPORTUNITIES IN NEIGHBORHOOD SELECTION

Moving on to the gap in investment in overlooked communities or “investment deserts.” The investable universe of total US real estate is approximately US$17 trillion,[3] but only $4 trillion[4] is professionally managed, indicating lack of access for big swathes of commercial real estate to efficiencies and expertise that can improve returns outcomes. Although many cities have made big leaps in economic growth in the last decade, this opportunity is often inequitably distributed at the neighborhood level. Years of redlining, public and private disinvestment, and negative perceptions have denied many centrally located urban and inner suburban neighborhoods access to resources, services, and development opportunities.

Some of these neighborhoods have seen investment inflows recently as changes in demographics and preferences supported demand for unique live/work/play neighborhoods that were close to CBDs. However, these inflows raise other issues of displacement of existing households and exclusion from building wealth generated from rising property values. Many such neighborhoods remain “investment deserts” and lack resources to attract new development to benefit existing renters who remain attached to their communities for social and personal reasons. Encouraging growth while preserving affordability for existing residents is key to providing opportunity and creating more equitable communities. By developing businesses, services, and residential units that anchor neighborhoods, more investment dollars will flow into them.

There is merit in investing in overlooked neighborhoods, where the tenant supply/demand dynamics are heavily tilted in favor of solid demand with barely any new supply in recent years. At the same time, density is critical to building community, promoting sustainability and fueling growth. There is opportunity to add new, high-quality, and mixed-income housing and retail investments within these communities, while preserving affordable rents and community control.

How do investors bring capital to these “investment deserts?”

Investors can broaden their horizon by focusing on affordable neighborhoods and projects as well as metros that are not on the radar for institutional investors. Investing in projects with better alignment to community goals and local economic development efforts championed by local governments that can potentially reduce land costs, minimize entitlement risk for higher-density product, and improve lease-up potential. Lastly, there tends to be less competition from capital markets because these neighborhoods are often overlooked by traditional institutional capital.

INCLUSIVE AND DIVERSE—OPPORTUNITIES

IN DEVELOPER INCLUSION

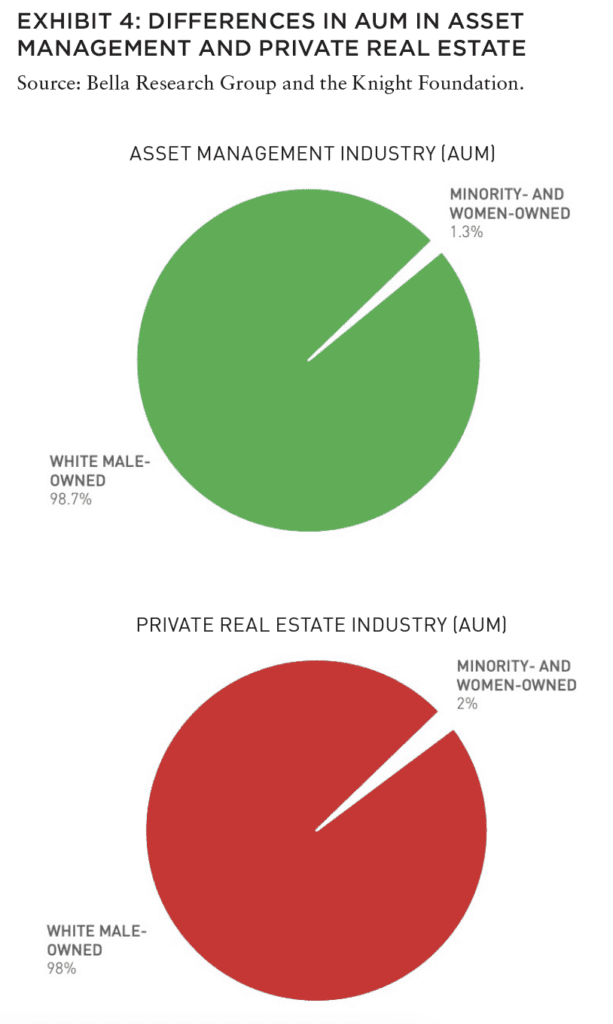

Finally—it is also obvious that there is a need to open the door wider to let in diverse voices to help build and bridge those gaps in product types and in those neighborhoods. Minority-owned manager’s access to capital is key in addressing systemic underinvestment in minority communities. People of color comprise 40% of the US population, but direct less than 2% of the investment capital. A study released by Bella Research Group and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation in 2019 found that firms owned by women and minorities managed just 1.3% of assets in the US$69 trillion asset management industry, though their performance is not statistically different from the industry as a whole.[5] For real estate, using Preqin data, along with hand-compiled lists of diverse firms, women- and minority-owned firms accounted for 0.8% and 1.2% of total real estate AUM (Exhibit 4).

Real estate investment is especially impactful as it informs business investment, job creation, community benefit and generational wealth resultant from home price appreciation. Thoughtful, intentional action is required to affect these trends as leadership at the top commercial real estate firms remain majority White, from investors to developers, lenders, and brokerages.

Support for local real estate developers that align with communities of color but who are caught in a struggle to access capital is a critical piece of the puzzle. Due to their ability to leverage deep, local, and long-term relationships and identify opportunities missed by traditional capital, these developers tend to have lower cost bases and the potential to generate higher returns.

Diverse developers also tend to have expertise in traditional affordable housing formats and operations that are more complicated to execute on from an entitlement and capitalization standpoint than commodity market-rate projects. Not only are these developers connected to their neighborhoods, but they also tend to hire other minorities for development-related jobs ranging from contractors to appraisers that also tend to be under-represented, creating a multiplier effect that may not be measured by a singular “return” metric. This is also a powerful way to develop human capital in a sustainable way by providing access to opportunities in the building and construction trades.

Development of housing infrastructure is not only essential relative to affordability issues, but also critical given the age of the existing stock and looming impacts of climate change.

The good news is that there is a real push to move past the notion of perceived risk and seek to bolster investment in communities and people that have been in the blind spot for many investors. There are signs that capital is also ready to want more from their investment than just financial returns. To the capital of today and tomorrow, intent and execution matter also. At the same time, the notion of what is risky is also being recast and reconsidered. There is a growing realization that inclusive development that lifts up overlooked communities is sustainable, equitable, and profitable—not just by the metrics of traditional financial results but, more importantly, by creating true social impact.

—

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Shubhra Jha is a Principal at Standard Real Estate Investments, a minority-owned and -controlled investment manager founded on the idea that those who help deliver a better world will see better financial returns.

—

NOTES

1. “America’s Rental Housing,” Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, 2020, jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/reports/files/Harvard_JCHS_Americas_Rental_Housing_2020.pdf

2. Whitney Airgood-Obrycki, Alexander Hermann, and Sophia Wedeen, “The Rent Eats First,” Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, January 2021, jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/research/files/harvard_jchs_rent_eats_first_airgood-obrycki_hermann_wedeen_2021.pdf

3. “Estimating the Size of the Commercial Real Estate Market,” Nareit, 2019, reit.com/sites/default/files/Size%20of%20CRE%20market%202019%20full.pdf

4. Bert Teuben, Razia Neshat, “Real Estate Market Size,” 2019, msci.com/

documents/10199/035f2439-e28e-09c8-2a78-4c096e92e622

5. Josh Lerner et al., “2018 Diverse Asset Management Firm Assessment,” Bella Private Markets, January 2019, knight.app.box.com/s/5l2s2pi75b6qoip5uo47zsiawk133vud